To play the piano is to play weight transfer. Poise and freedom, alertness and awareness, sound and technique all flow from weight transfer. The piano is there, and I’m here; my back and legs, my shoulders, my head and neck are all here. I lift an arm and drop it, aiming to play a single note at the piano—that is, to transfer my weight onto the piano key and create a sound. No, it’s not simple at all. There are many obstacles to the mastery of the gesture and to its application to piano playing. I’ll stiffen my neck without knowing that I’m doing it; I’ll block my shoulders; I’ll hold instead of releasing; I’ll be afraid of hitting the wrong note, and—believe it or not—I’ll be afraid of looking funny and sounding too good for my breeches. It takes forever to master weight transfer, and naturally it must start with the First Lesson in Weight Transfer. And because it’s so important and so difficult to learn it, the devoted pianist goes back again and again to the First Lesson.

My beloved piano teacher, Alexander Mion.

In my youth I studied aikido on and off, in various countries and under various teachers. There’s a sort of warm-up exercise that seems banal if I describe it: sit on the floor, bring the soles of your feet together and as close to your crotch as possible, keep your knees down on the floor, lean forward. One of my teachers once told us that it had taken him 25 years to understand all the implications of the exercise. The First Lesson of aikido must be repeated thousands of times until one learns it. And then the First Lesson must be repeated thousands of times after one learns it.

Morihei Ueshiba, the founder of aikido.

As schoolchildren, some of us learned that the primary colors are red, yellow, and blue, which we can mix to obtain all other colors. Wrong, wrong, wrong! Depending on the technical perspective you take, the true primary colors are red, green, and blue. Another perspective affirms that the true primary colors are cyan, magenta, and yellow. The First Lesson of Color Theory and Practice is much more involved than we assume.

The parrot is called Mojo.

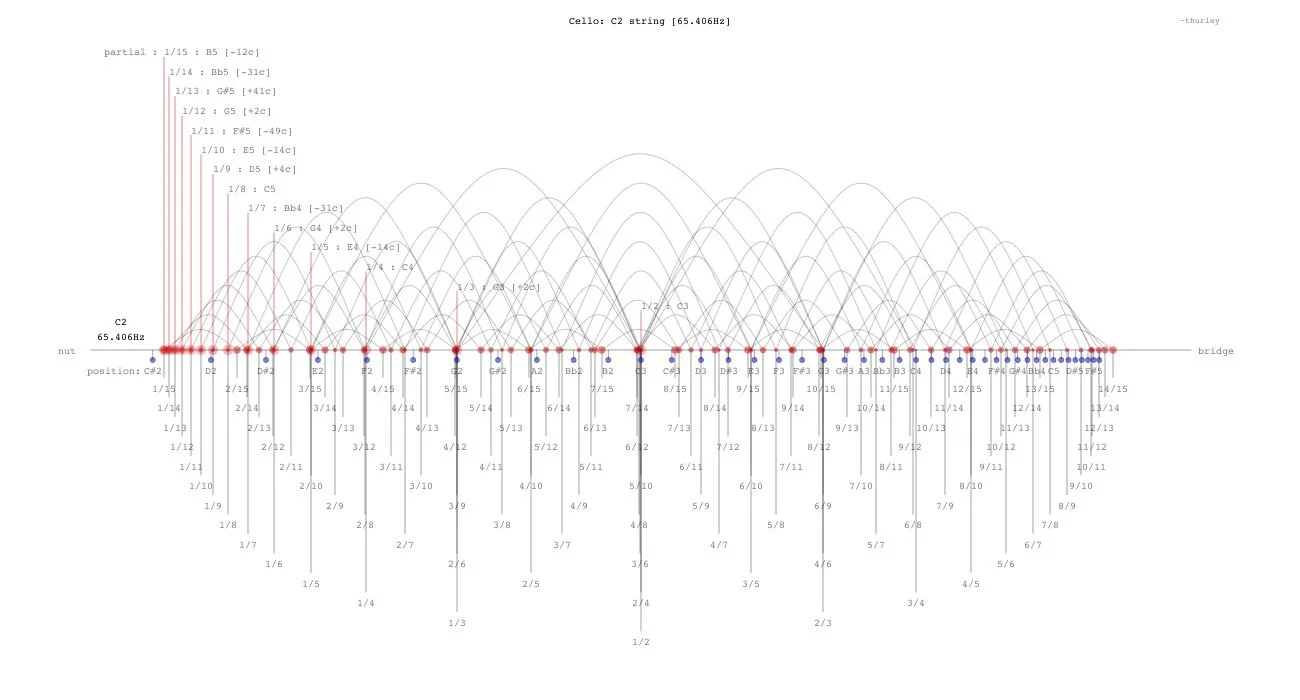

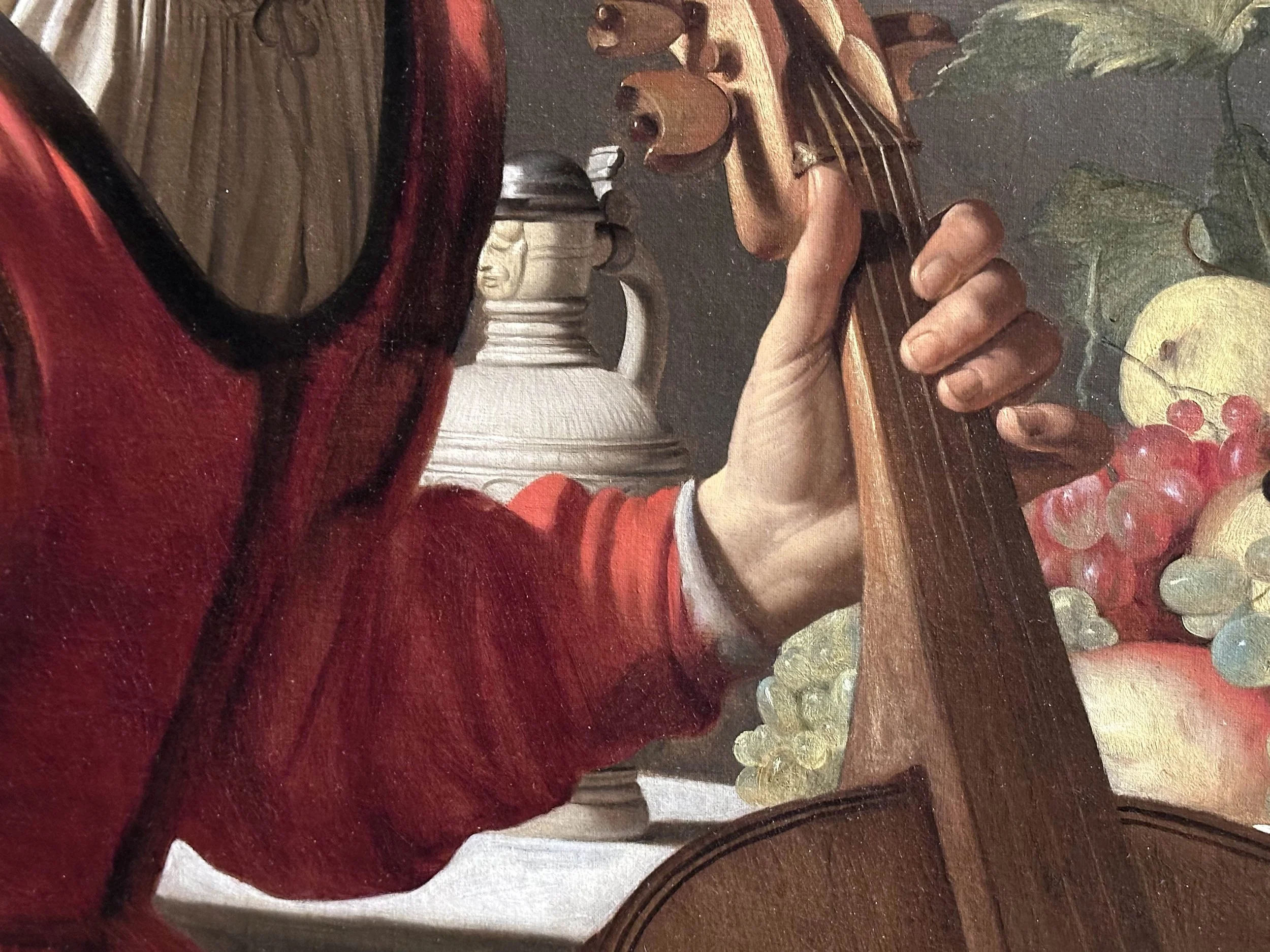

The image below shows you a string from the cello, with a certain number of harmonics mapped on the string. If you aren’t a musician, you won’t understand anything, although you might still appreciate the elegance of the graphics. If you are a musician, you might not understand anything either if you haven’t learned the basics of fundamentals and harmonics. And yet, to make music is to handle fundamentals and harmonics with every sound you make, every piece, every song, every improvisation, every last thing, everything. It’s a mistake for musicians to skip the First Lesson of Harmonics, and to skip the second and the third and the nth time taking the First Lesson of Harmonics.

With thanks to Oliver Thurley.

Every first lesson is like a portal, inviting you to pass from incoherence to integration, from awkwardness to smoothness, from surface to depth. For those of us with an innocent and curious disposition, the first lesson is the best lesson, the most intriguing, the most fun. When you “get” weight transfer, you “get” the meaning of coordination. When you “get” the primary colors, you “get” visual perception, you “get” art, you get “the world is alive and full of the most incredible things.” When you “get” fundamentals and harmonics, you “get” the universe of sound, vibration, consonance and dissonance, resonance, harmony, counterpoint, the whole of music.

To absorb the first lesson, you need a clear mind and a glad heart. The mind, however, has a mind of its own (called Confusion) and the heart has a heart of its own (called Don’t Talk to Me I’m Busy Pumpin’ Pumpin’ Pumpin’). This is the very meaning of the first lesson: the taming of Confusion and Pumpin’. How many first lessons do your mind and heart need until they’re ready to learn the First Lesson?

Happy New Year, and Happy New First Lesson.

In January and February, 2026 I’ll be giving myself the First Lesson of drawing: handling pencils and pens, caressing sheets of paper, looking, seeing, and enjoying everything involved in the act of drawing. You’re welcome to join me.

©2026, Pedro de Alcantara