Count out loud from one to twelve. It’s a nothing exercise, right?

One two three four five six seven eight nine ten eleven twelve.

You’re about to find out that it’s an everything exercise: a portal from dismissal to embrace, from hurry to timelessness, from the profane to the sacred.

Consider the number 12 and how present it is in your life: the twelve months, the twelve signs of the zodiac; the twelve hours, and the other twelve hours, making up a full day; the twelve apostles, the twelve tribes of Israel, the twelve Olympian gods of the Parthenon; the twelve members of the jury, which famously became Twelve Angry Men, the fabulous film directed by a young Sydney Lumet. And let’s not forget the dozen eggs.

(And the twelve tones of the chromatic scale, and the twelve fundamentals of the circle of fifths.)

We won’t elaborate the point any further, but we’ll agree (won’t we!) that the number 12 is incredibly powerful from a symbolic and metaphysical point of view. It’s central to our existence.

Let’s spend a little time with mathematics. We can divide 12 by 12, 6, 4, 3, 2, or 1, giving us a wide variety of symmetrical subdivided combinations. The number 10, in comparison, can only be divided by 10, 5, 2, or 1. It’s less flexible, so to speak. Here's an illustration of how twelve can be four times three or three times four.

The rhythms of a language contribute to its prosody. The prosody of English, for instance, is very different from the prosody of Hungarian: stresses, inflections, and groupings of syllables and words make it possible for us to tell, immediately, if someone is speaking English or Hungarian. Here’s a very short poem spicing up the prosody of your counting.

ONE | two | three.

One | TWO | three.

One | two | THREE.

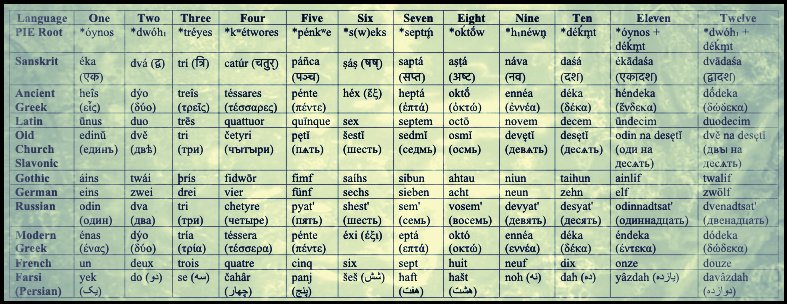

Numbers have names. The number 3, for instance, is called “three.” Counting is a version of naming. Names come with stories and histories. Think of a few everyday names, like Sarah, Pedro, Miguel, and Elizabeth. Look them up on the Internet, and you’ll see that these names have existed for thousands of years and have passed through the Bible, through royal lineages, through wonders and miracles, through joys and terrors. The names of the numbers also come with incredible stories and histories. More than six thousand years ago, a language was spoken in the region that today we call Ukraine. The people who spoke that language traveled widely and disseminated their culture. And you know what happened? Their language had babies. Greek, French, Farsi, Sanskrit, and dozens of other languages are wonderfully complex derivations of a single language, which linguists call Proto-Indo-European.

Whenever you say the name of a number out loud—“three,” “seven,” “one hundred and forty-four”—you’re manifesting a millenary linguistic tradition that binds together many cultures and many people. To count is to be part of something unimaginably gigantic, timeless and ever-present.

Counting requires vowels, diphthongs, and consonants, a wealth of sounds in marvelous combinations. Some of the richness might escape your attention at first. For instance, “one” stars with an unwritten consonant sound, kind of like this: “wone.” Did you know—did you know!—that you’re forever pronouncing unwritten consonant sounds?

Count out loud super-slowly, lengthening every lengthenable sound and enjoying every microsecond of your over-commitment.

Wwwwooooonnnnnne, twoooooooooo, thhhhhhrrrrreeeee . . . .

To count out loud is to engage the lips, tongue, jaw, pharynx, larynx, glottis, lungs, diaphragm, and 144 other body parts. Counting is physical, like dancing and martial arts.

Muscles, nerves, tendons, joints;

movement, energy, flow, effort;

poise, pleasure, sound, silence.

To count is to breathe. It’s such a big subject that I’ll limit myself to a possibly helpful simplification: baby (perfect natural unconscious reflex), adult (awkward gasping asthmatic hyperventilation), master (perfect natural conscious reflex).

One, two, three . . . and I breathe, like a baby or like a master.

Four, five, six . . . and my ribs and lungs move of their own accord.

Seven, eight, nine . . . and I receive air, oxygen, prāna, and love.

Ten, eleven, twelve . . . and I’m ready to cry with happiness.

Chant your numbers calmly, at a very moderate pace, on a pitch that doesn’t change, taking sweet loving prosodic breaths after two, three, or four numbers. You have become a chanter in a sacred setting, regardless of who you are and where you are.

This exercise is part of “The 5-Minute Voice,” my series of clips for all comers addressing vocal creative health. Would you like to know more about it? Click here.

©2025, Pedro de Alcantara