Little kids playing engineer in the sandbox take their business seriously—I mean, the business of play itself. The kids are invested in the moment, attentive, careful. It’s not a sandbox, do you understand? It’s the world. And don’t interrupt us, because sand is divine and playing with it is urgent and meaningful. In play we build; in play we connect; in play we live.

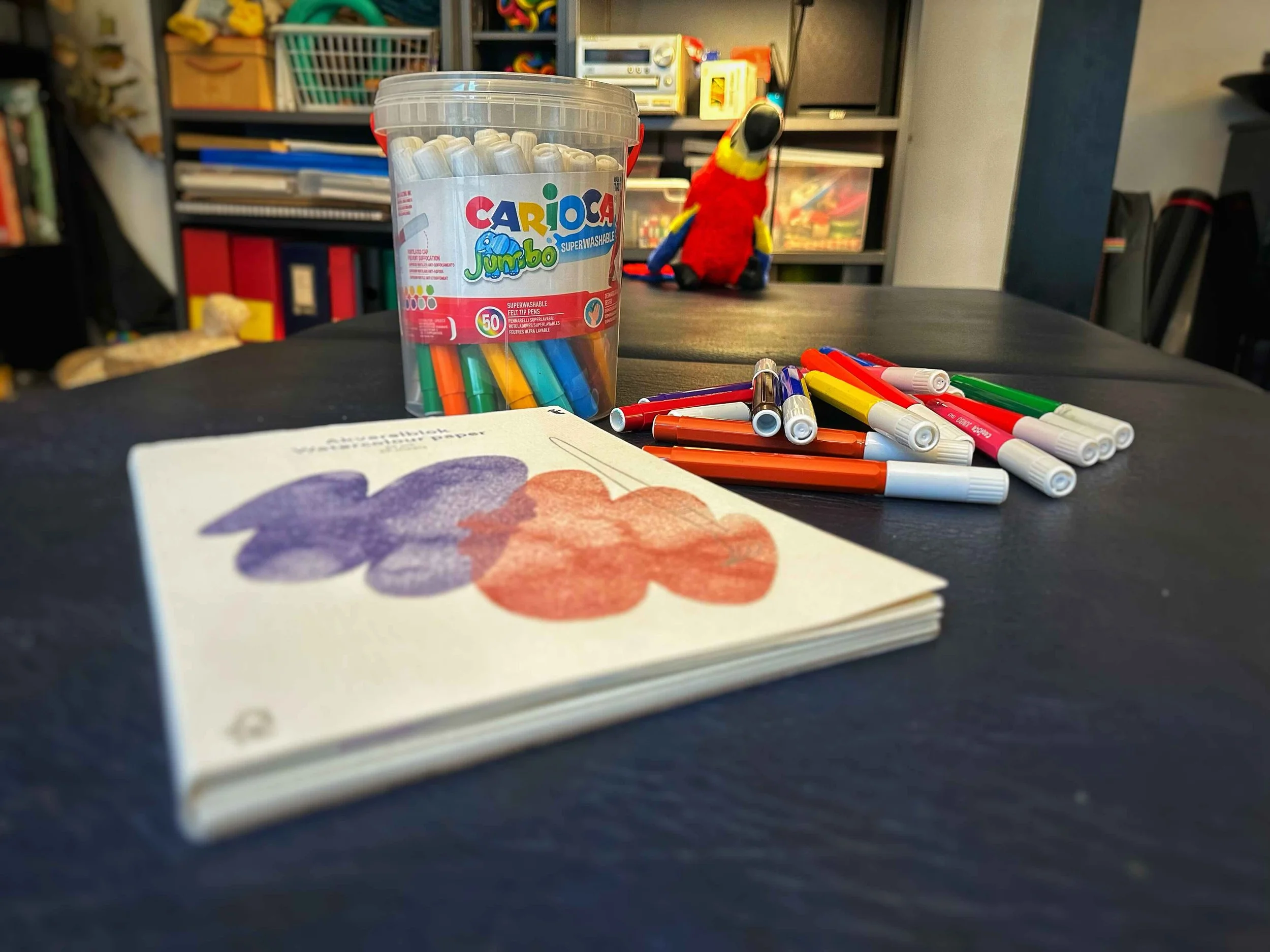

A couple of years ago, circumstances led me to buy a bucket of inexpensive markers from the supermarket. (Actually, “Circumstances” is one of the nicknames for “Destiny.”) They were made in Italy—the land of Michelangelo and da Vinci, of Fra Angelico and Giotto. Fifty markers, 25 colors, two markers of each color; water-soluble, non-toxic, and gluten-free. Stick the inky tip in your mouth and taste it. You won’t die.

The bucket sat there, in the sandbox tool shed of the mind (actually a bookcase in my living room). From time to time I’d pull a marker out and do a bit of nothing with it. Then “Destiny” (Circumstances) led me to sense, or feel, or understand, or discover, that if you make a drawing using a water-soluble marker, you can then wet the drawing a little and turn it into a watercolor work of art. Bingo Giotto!

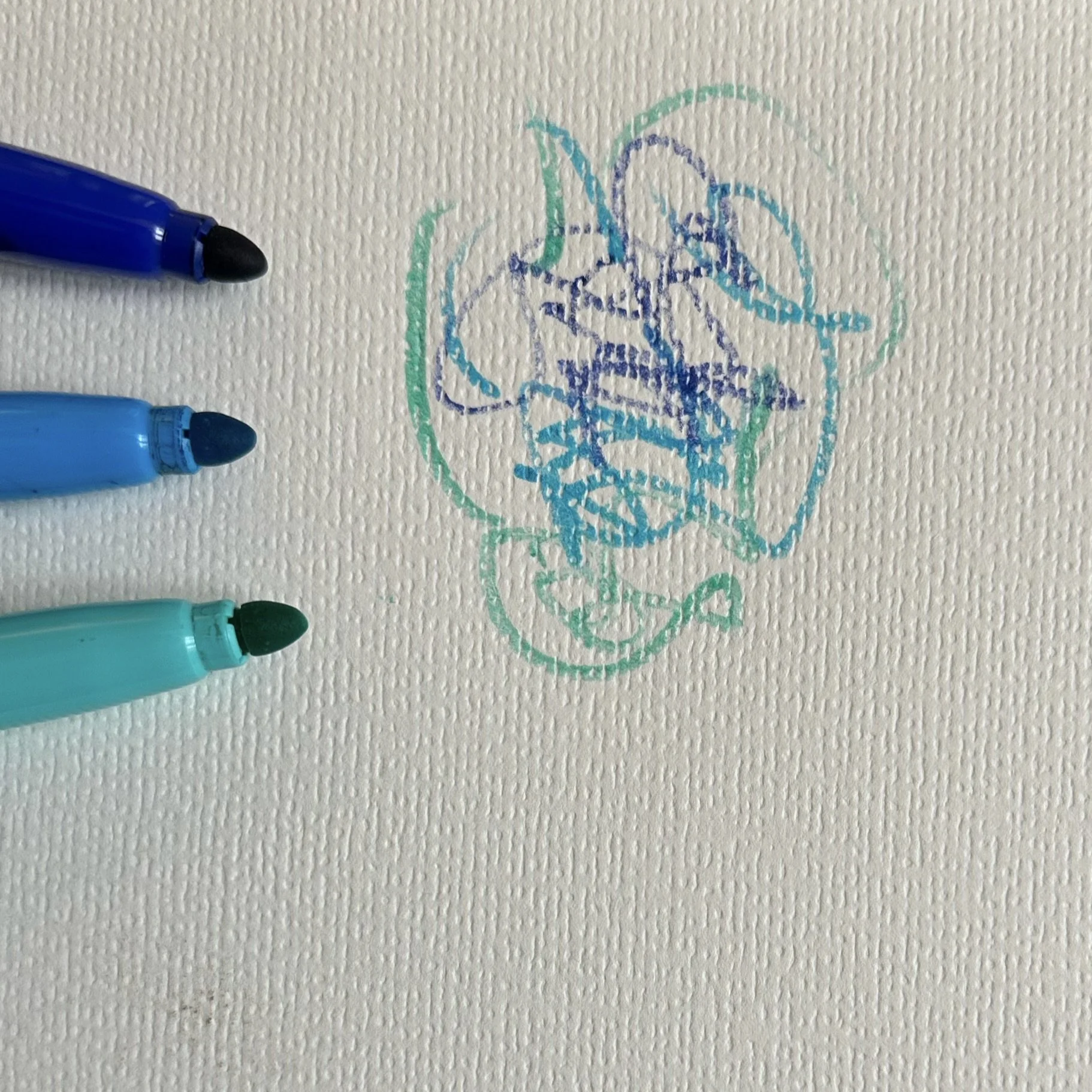

Mix and match the markers that you use for your drawing. When you wet the drawing, the colors will bleed. (Play and Bleeding were lovers in a past life.) There’s an interaction of paper, ink, and water; you can’t control everything; the results are surprising; Giotto laughs in delight and thanks Circumstances for another gift, another invention, another organized accident of shape and color.

I forgot to tell you that Circumstances had led me to buy some watercolor paper from a chain store at a train station in Basel, Switzerland (land of Holbein the Young, of Erasmus, of Roger Federer). I was traveling and I needed to get a gift for my wife back home; don’t tell her, but the watercolor paper was inexpensive. And good! Nicely dimensioned, sort of thick and textured, friendly to the touch, friendly to the marker. I bought my wife a watercolor sketchbook, and another for my wife’s husband. You know—family dynamics. Keep everyone happy.

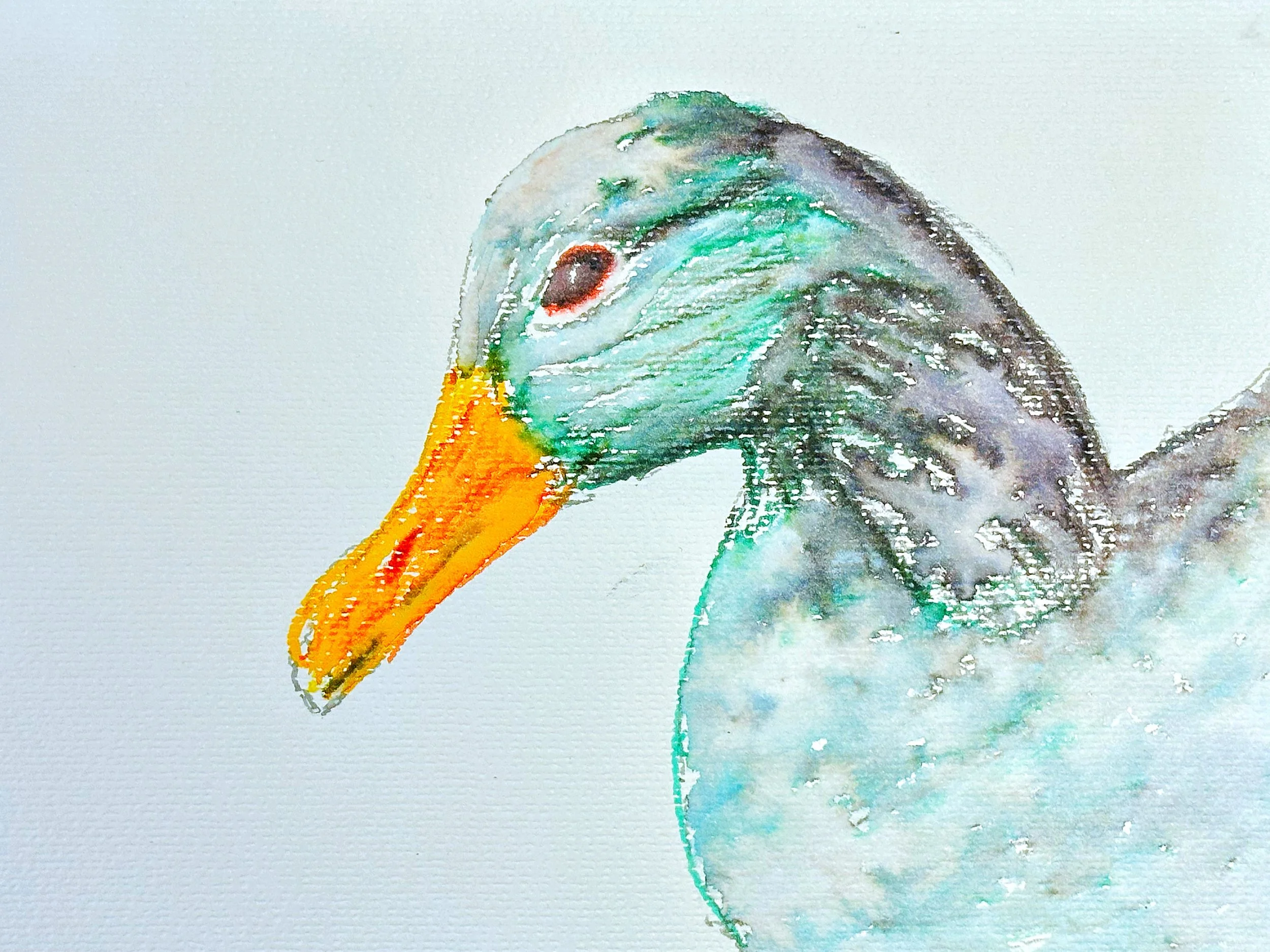

I thought I’d draw a bird with a black marker, using a photo for guidance. A few strokes here and there; a little shading; quick and improvisational, like Giotto working on a fresco in a church in Florence, exactly like Giotto, I’m telling you! Then I took a small brush from my sandbox toolshed and wetted or daubed my drawing with water without thinking much at all, as if tenderly caressing the bird. And Circumstances gave birth to another work of art, depending of course on how you define art.

The bird got me going. I did another drawing, and another. There was something easy and pleasant about the procedure. Watching the colors bleed one onto the other when I wetted the paper was very satisfying. It was as if water itself, or Water Itself as we say in the old country, was doing the creative work for me or on my behalf. I did the drawing; I didn’t do the drawing; both are true.

Shall we draw a numbered list of conclusions from my encounter with Giotto’s ghost?

1. Circumstances are a good friend to your creative mind.

2. Inexpensive materials have their own merits, but you have to take them “as they come” or “as they are.”

3. A quick stroke of the marker on a sheet of paper, without much calculation or forethought, is more productive than asking yourself unhelpful questions at unhelpful moments.

4. Art is difficult to define.

5. No, art is impossible to define. But grappling with art itself and with the way you define it can be very productive. Just because something is impossible doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t try to do it.

6. Did you know that repeated practice can sometimes improve your skills?

7. And yet, skills are secondary to the first impulse, the willingness to accept advice from Circumstances, the appreciation—no, the love—that you have for the sand in the sandbox. You don’t practice your skills; you practice your desire to play.

©2025, Pedro de Alcantara