At an art show you can “see the art” or “see the show.” Truth be told, there are hundreds of ways of looking at any situation, but for now we’ll embrace this either-or simplification.

One of the great Paris museums, the Cité de l’architecture et du patrimoine, is housed in a huge 1930’s building perching on a hill overlooking the Eiffel Tower.

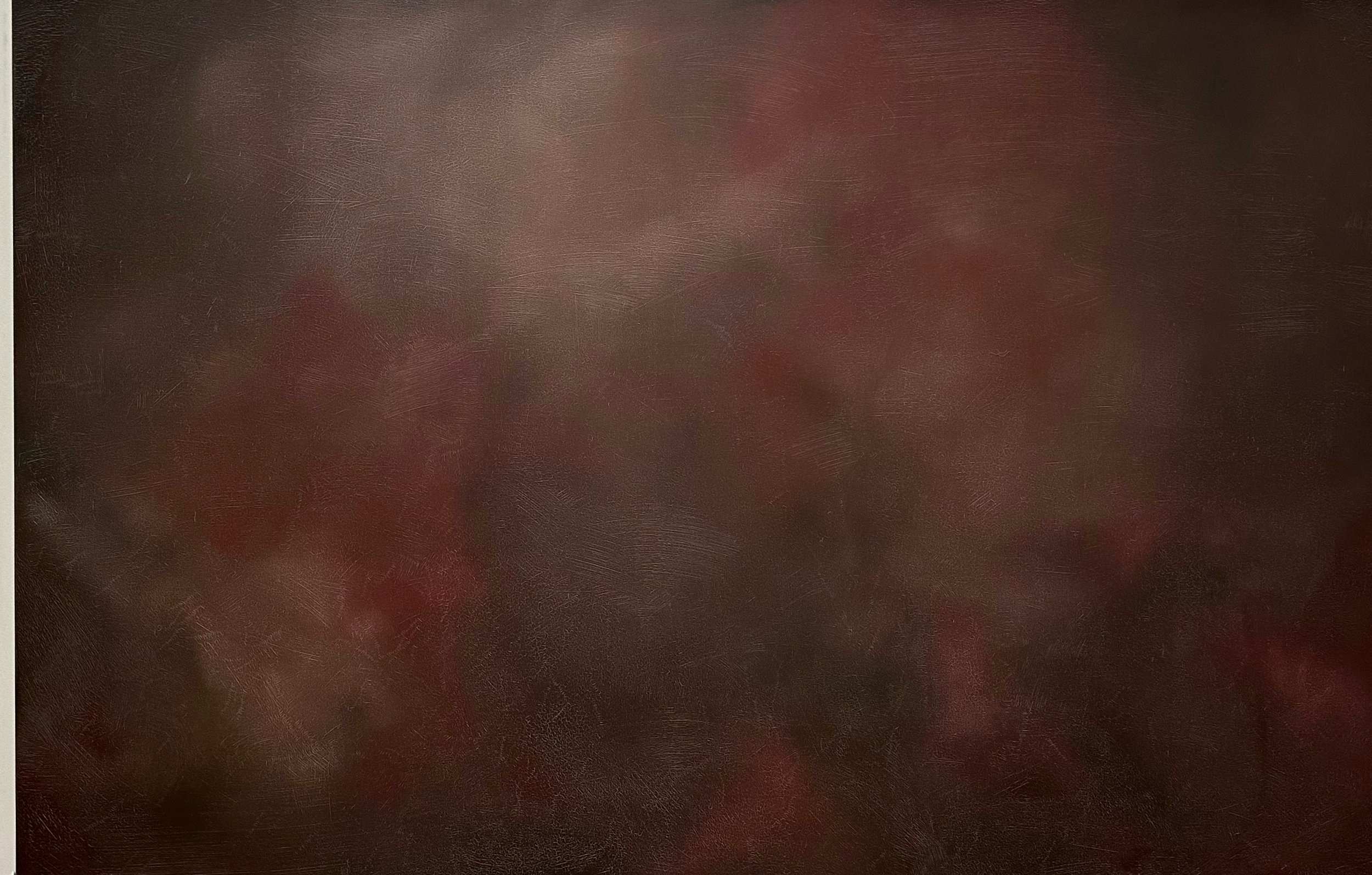

The museum contains reproductions of statues, porticoes, and other architectural features from historic monuments. On its top floor there’s a warren of windowless galleries with reproductions of frescoes. One of the galleries is under a high domed ceiling. Other galleries are reminiscent of monks’ cells, being “constrained and restrained.” Along these galleries, the museum put on a show of twenty-three Color Field paintings—large works in which the canvas is dominated by blocks or splashes of color. The artists included Robert Motherwell, Morris Louis, and Helen Frankenthaler, among others.

The paintings were wonderful, the setting was exquisite, and the dialogue between the artwork and the physical space was inspired and inspiring. I visited the show three times in a period of two weeks. During the visits I was often completely alone. I would stand in front of a painting for ten minutes without bothering anyone. Discovery, pleasure, astonishment; meditation, perception, insight. I was so happy I could have cried.

Another great Paris museum is the Fondation Louis Vuitton, housed in an ambitious labyrinth of a building by Frank Gehry that opened in 2005 in the Bois de Boulogne. It tends to put on gigantic retrospectives of a single artist such as Mark Rothko, Cindy Sherman, and David Hockney. The shows are often too big, overwhelming, exhausting. And usually they’re quite crowded. The most recent show featured Gerhard Richter, a prolific, accomplished, and very famous German artist. I was familiar with his work and thought that I liked it very much, but the retrospective led me to change my mind. A French thinker once stated that "facility is nature’s most beautiful gift, provided that one never uses it." It feels to me that Richter uses and overuses his tremendous facility, to the detriment of meaning. Don’t get me wrong; Richter is a great artist and I did really love a handful of his paintings.

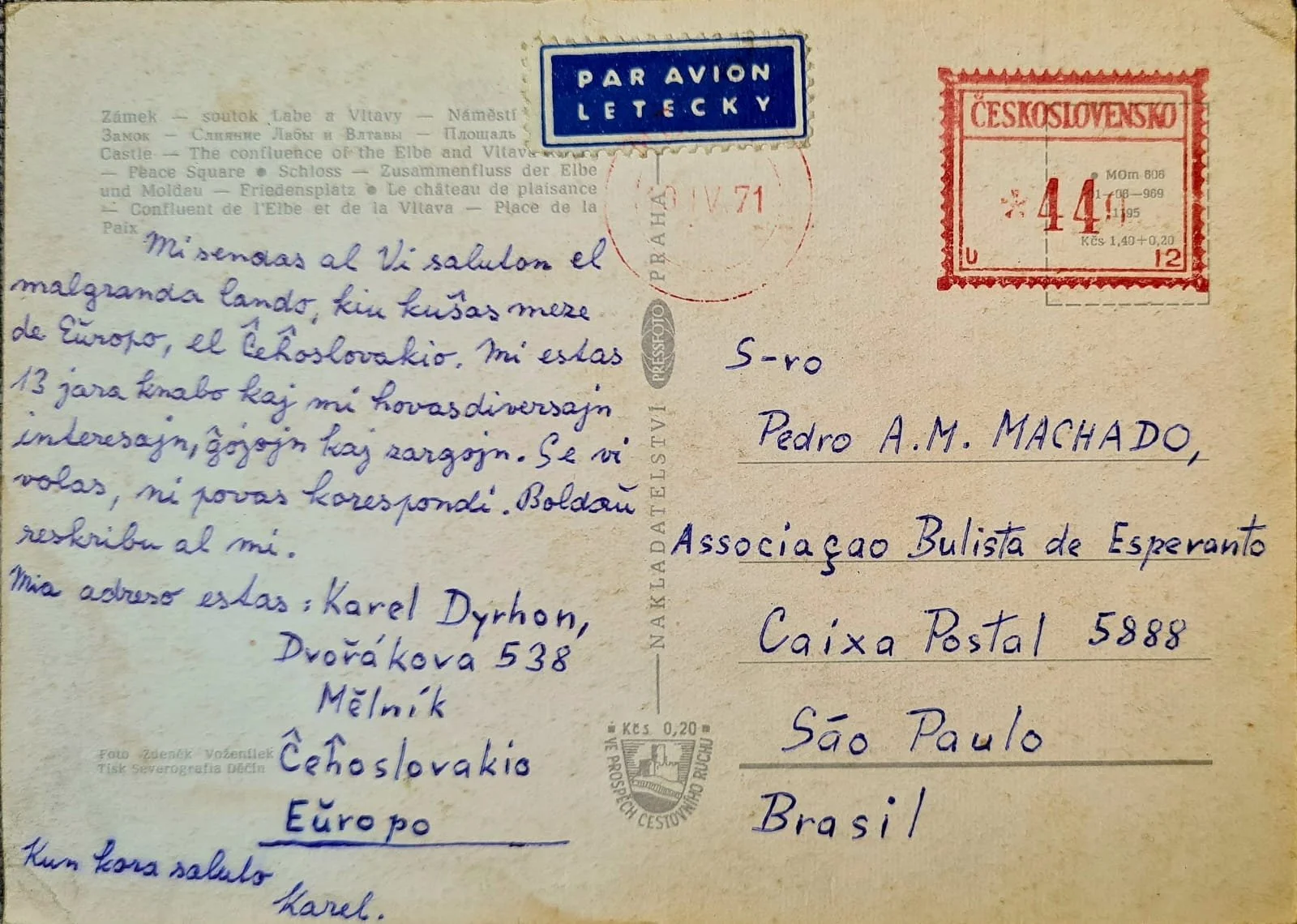

Gerhard Richter.

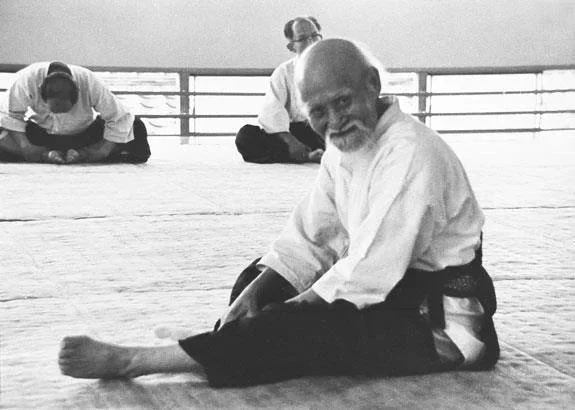

I visited the show twice. On my second visit I wasn’t willing to look too closely at the art, and I decided to turn my attention away from the art and toward the flow of museum goers, the endlessly varied faces and postures of the Parisians and tourists and little kids crowding every nook and cranny of the labyrinthine museum.

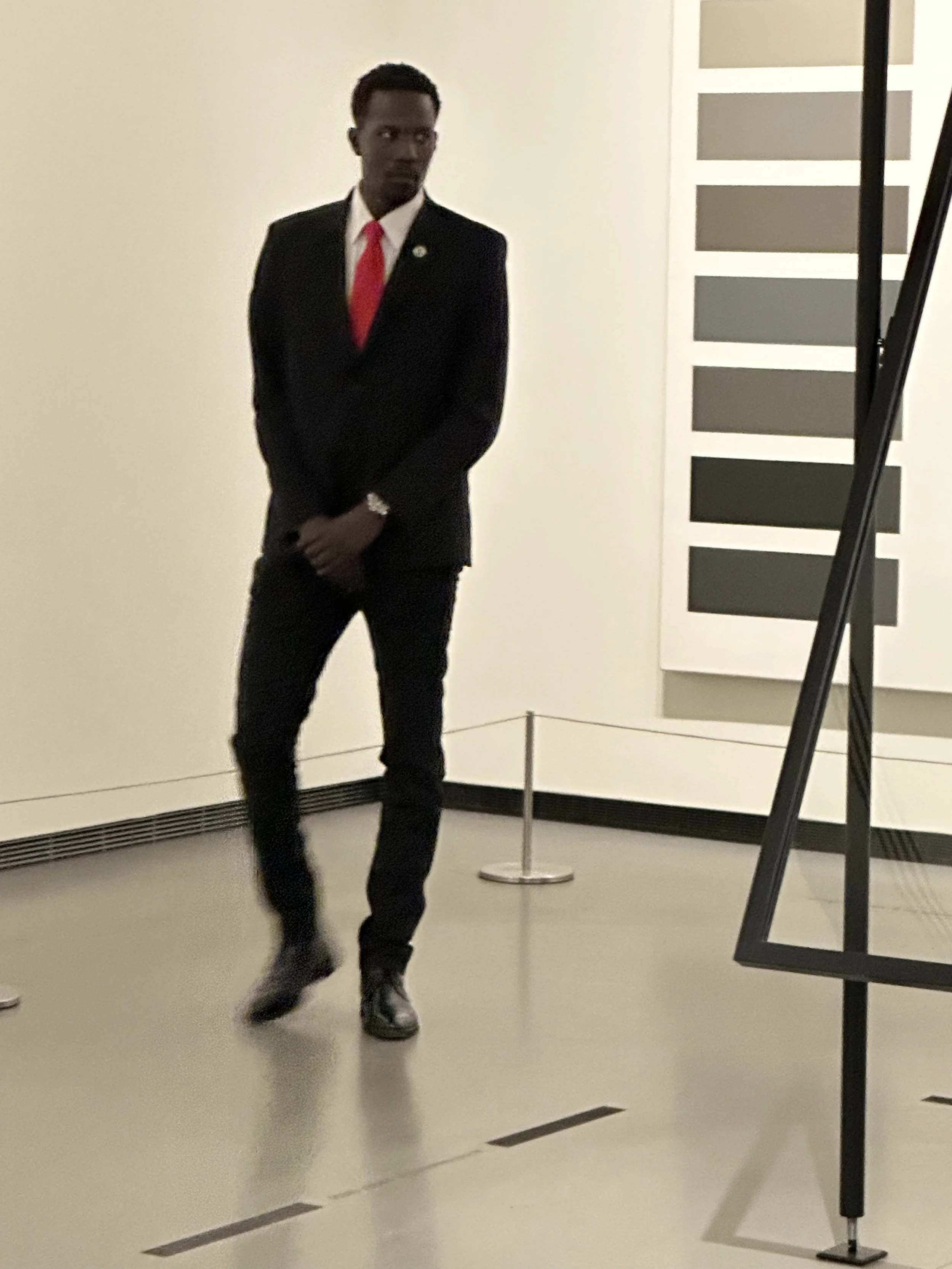

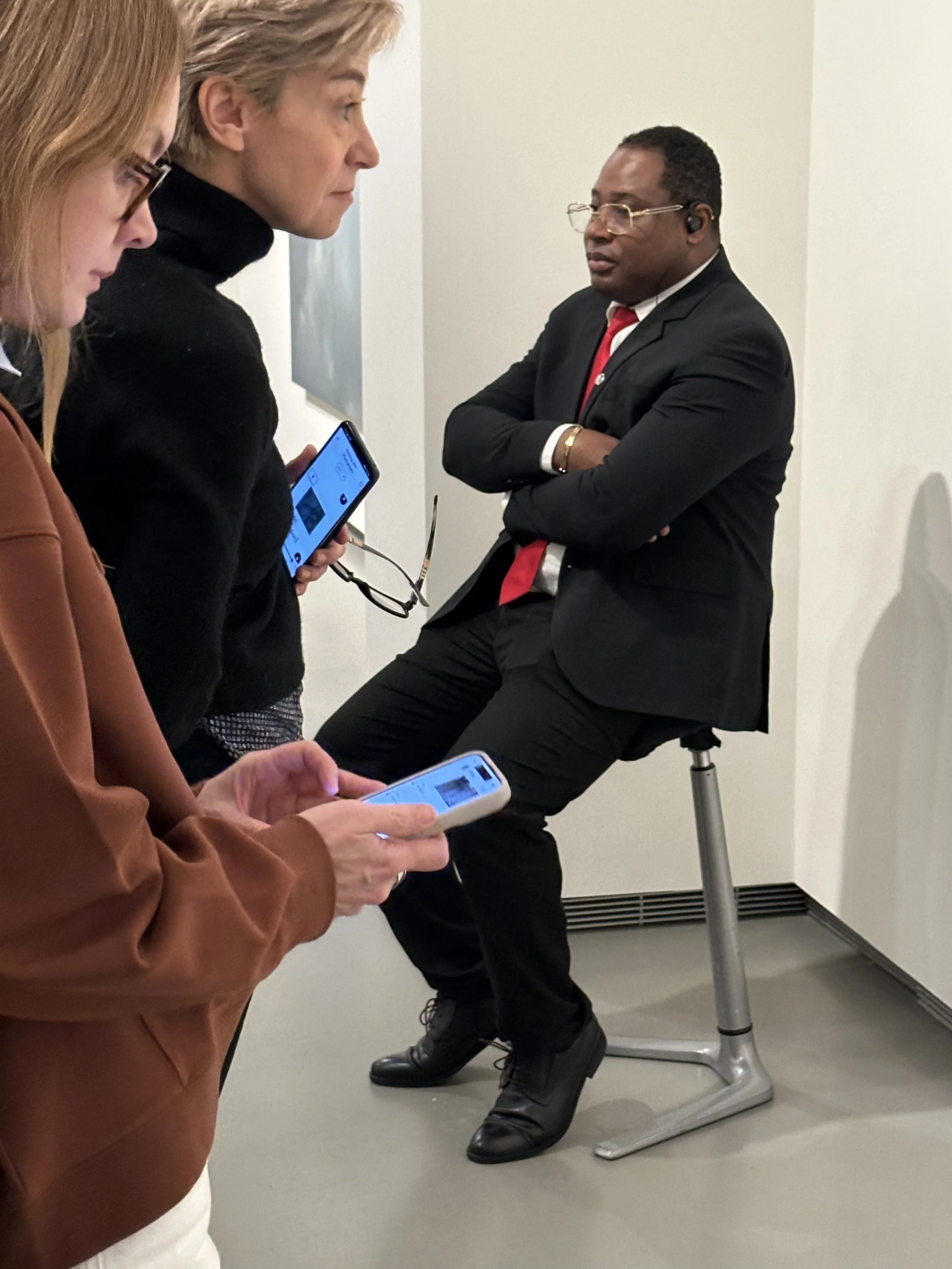

I focused on the museum guards, who have long fascinated me. Museum guard is a demanding job, not only because you’re responsible for the safety of the art and of the museum goers but also because you risk being bored out of your skull. Six or more hours of standing here and there, in airless or windowless environments, day after day, year after year?

I sometimes talk to museum guards and hear their interesting stories, but on this visit I decided to keep a sort of distance from them and surreptitiously take their portraits. It’s as if I was curating an art show of my own, perhaps titled RICHTER | GUARDS.

Richter famously transformed photos into paintings, and famously painted themed series of realistic portraits. Call me a fool, but I think my little photo essay here is vaguely and definitely Richterian. I’m glad I went to see the show.

©2026, Pedro de Alcantara