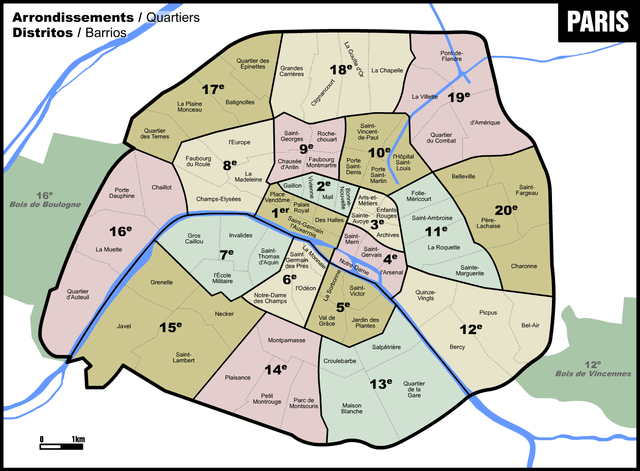

The calendar is a strange beast. Stars and planets are dancing in the infinite universe, and the calendar somehow must capture the rhythms of the dance and state, unequivocally, that this is 11:11 AM on Tuesday the 24th of December, 2024. Crazy! The inhabitants of Kiritimati say that it’s Wednesday. Our friends in New York City claim it’s 5:11 AM, much too early to have a metaphysical discussion about the calendar. And my siblings out there in Brazil say it’s not Tuesday at all but terça-feira.

The calendar is a liar, and only fools would take it for its word. Actually, let me rephrase this so that some of the fools walking the streets of Kinshasa (11:11 AM), Addis Ababa (1:11 PM), and Kathmandu (4:11 PM) don’t get mad at me.

There once was a man from Kathmandu,

Who thought he could dance like a guru.

But he tripped like a fool,

Fell right in the pool,

And now his best move is “peek-a-boo!”(by Ch. George P. Tee)

The calendar is an abstraction, trying to capture and fix a shapeshifting entity called Time. We like the calendar; time zones have made the world much easier to navigate, literally and symbolically; it’s good to have labels like Tuesday and mardi and terça-feira and Dienstag and Jumanne to help us know where in the week we stand; it’s wonderful that the Mayan and the Gregorian and the Julian calendar don’t agree on anything. Maya says the future is now, Gregor says the future is tomorrow, Julius says “Pizzam pro Natale volumus.”

My apologies to the fools in Kabul (2:41 PM). This blog post is very confusing, just like the calendar. Someone is having an early breakfast in Caracas (6:11 AM) at the same time that someone else is having a late dinner in Adelaide (8:41 PM). It isn’t right, is it!

I grew up with the 24-hour clock. After twelve noon there comes 13:00. It makes you think, feel, breathe and live differently from someone who grew up with that AM / PM thing, where twelve noon is follow by 1 PM. What the hell, “one” comes after “twelve”? Can’t you count????

The calendar itself has no feelings, probably. Humans have feelings, probably or maybe even surely. I think I have feelings (which is what Descartes meant to say, but he wasn’t having a good day). Words like “solstice” make me sit up and take note. Equinox! Zenith! Nadir! I wish I knew exactly what they meant!

Let me give you two choices: (1) This blog post is talking about Christmas and New Year, and wishing you merry and happy. (2) This blog post is quite worrisome, Pedro. Are you okay? You don’t have to suffer just because your late mother was a psychiatrist. Call 1-800-MUSHROOMS.

©2024, Pedro de Alcantara