You can be alert and adaptable, to a varying degree; or confused and disconnected, also to a varying degree. Very alert and adaptable is desirable but not easy to achieve. Very confused and disconnected is problematic, don’t you think? So we all look for ways of going toward the desirable state, which is called by many names: embodied mindfulness, integration, happy-healthy, and I’m Okay Thanks, among others.

The journey isn’t linear. You can’t just take five little steps with no effort, and voilà! We humans are full of contradictory impulses, conflicting needs and wants, harsh circumstances, unconscious habits, tics, parasites, microbes, fauna and flora. Plus in-laws.

And yet, for millennia people have traveled the road to integration, and sometimes successfully. Many paths have been trod: prayer, ritual, sacrifice, discipline; concentrate on your breath, concentrate on your posture, concentrate on a sacred word. Procedures may include pilgrimage, reading, chanting, joining a group, leaving a group, waking up early, eating certain foods, dieting, fasting, drinking, not drinking . . . the list is long and fascinating, from Abstinence to Zen.

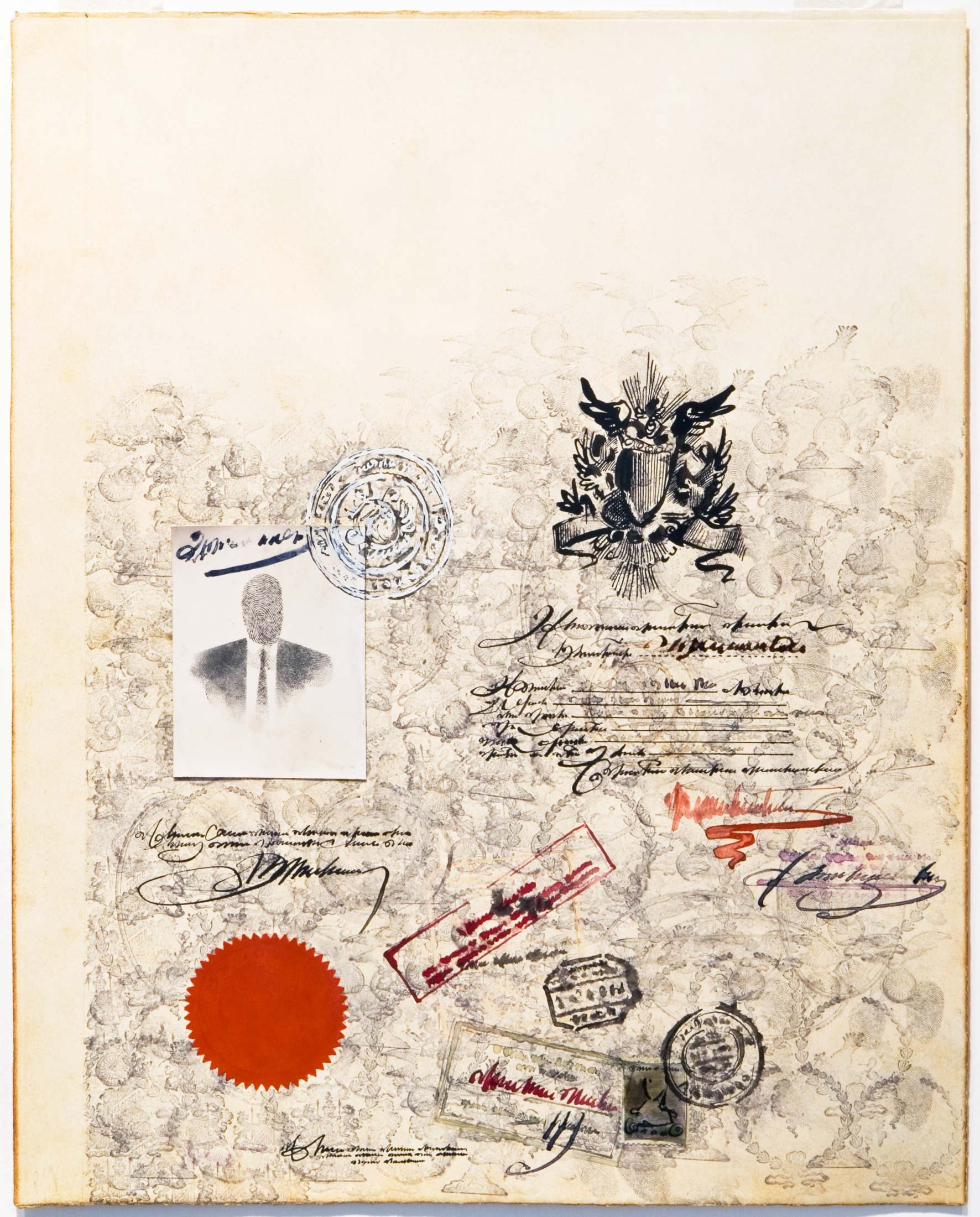

I believe that the passage from confused to alert can happen through any portal. You haven’t seen a friend of yours for a couple of years, and when you meet her again you sense she has changed in ways you can’t pinpoint. “You look different.” “Thanks for noticing. I took up ballroom dancing.” What is interesting is that she didn’t simply learn ballroom dancing; she worked on herself; she faced some of her longstanding fears about movement and sensuality; she reached out to other people and to the wider world; she learned a repertory of songs and dances; she became skillful at keeping a steady practice, going to dance several times a week; she passed from the private sphere of her home and her head to the public sphere of give-and-take in front of others; she traveled to Argentina for a tango workshop, and to Cuba for a salsa workshop. Her passport got stamped, if you know what I mean.

Artwork by Saul Steinberg, via the Saul Steinberg Foundation.

“You look different.” “Thanks for noticing. I’m learning puppetry.”

“You look different.” “Thanks for noticing. You won’t believe this, but I took up ping-pong.”

Any portal will do it, though different people prefer different portals. In the Japanese Zen tradition, for instance, portals have included archery, flower arrangement, the tea ceremony, and calligraphy. And sitting. Sitting will take you there. Ordinary life is full of portals that sometimes go unnoticed. To sort the laundry isn’t to sort the laundry; it is to work on yourself as you sort the laundry, discerning patterns, sensing textures and seeing colors, organizing objects, organizing your home, organizing your mind to accomplish a needed task, thinking about your children, having a million sensations and a billion emotions. Every sock tells a story. “My Hole, My Self.”

Hey, I said it already: people are full of contradictions. Becoming good at sorting the laundry won’t necessarily turn you into a model human being. We know that Zen masters can be irascible and unreasonable, that great painters can be suicidal drunks, that martial artists can be sadists who inflict pain on others for no good reason, that saints poop. “Perfection isn’t a human attribute; humanness is.” In life you’ll change and grow to the extent that you can. Existential change isn’t measurable. Working on yourself is a journey, not a destination. Poop like a saint.

My piano method will be published by Oxford University Press (OUP) in a few months. I think of it as a portal for you to work on yourself and become less confused and more alert, about the piano and music but also about yourself. You don’t need to be “good” in order to play the piano. You don’t need talent, previous experience, or anything at all; you just need to pass through the portal. It takes “willingness,” which in itself merits a whole blog post or encyclopedia since it’s the one requirement without which your passport won’t get stamped, if you know what I mean.

My portal is multidimensional. Ten chapters, plus introductory and concluding materials. Mysteriously wonderful little exercises that sound good and feel good to the fingers, hands, minds, hearts, and cosmogonies. Compositions, some four bars long, others seven pages long. Supporting video clips. Anecdotes, explanations, encouragement, attractive photos of children being children. There’s a photo of a baby goat, jumping. Wow, it’s one incredible adorable goat. My compositions have built-in space for you to think, sense, breathe, and decide how you’re going to play something, how you’re going to work on yourself, how you’re going to grow and change. Yes, every chapter starts easy, although chapter seven, for instance, is more elaborate and demanding than chapter one. Strange as it may seem, the method is suited to complete beginners and to concert pianists. The jumping goat is everyone’s friend.

Change-and-growth self-report: The six years during which I’ve worked on my piano method have been wonderful. My piano teacher and adoptive brother Alexandre Mion is wonderful. The production team at OUP is wonderful. The rehearsal studios that I frequent in Paris are wonderful. Walking from my home to the Studio Bleu 40 minutes away is wonderful. My students are wonderful. Receiving musical insights from unfathomable sources is wonderful. I’m still irascible and unreasonable, but there are days when I feel like a saint. It’s wonderful.