Think. Don’t think. Pay attention to other people. Ignore other people. Your goals determine your behavior. Your behavior impedes the achievement of your goals. Plan. Improvise. The artist is dead. The artist is immortal.

On a recent Sunday afternoon I visited the Rodin Museum in central Paris. My brother-in-law and his family were in town, and we all went there, together with my wife Alexis. While at the Museum I had an interesting experience. Or, to put it more precisely, I experienced yet again the twisty incomprehensible marvelousness of life.

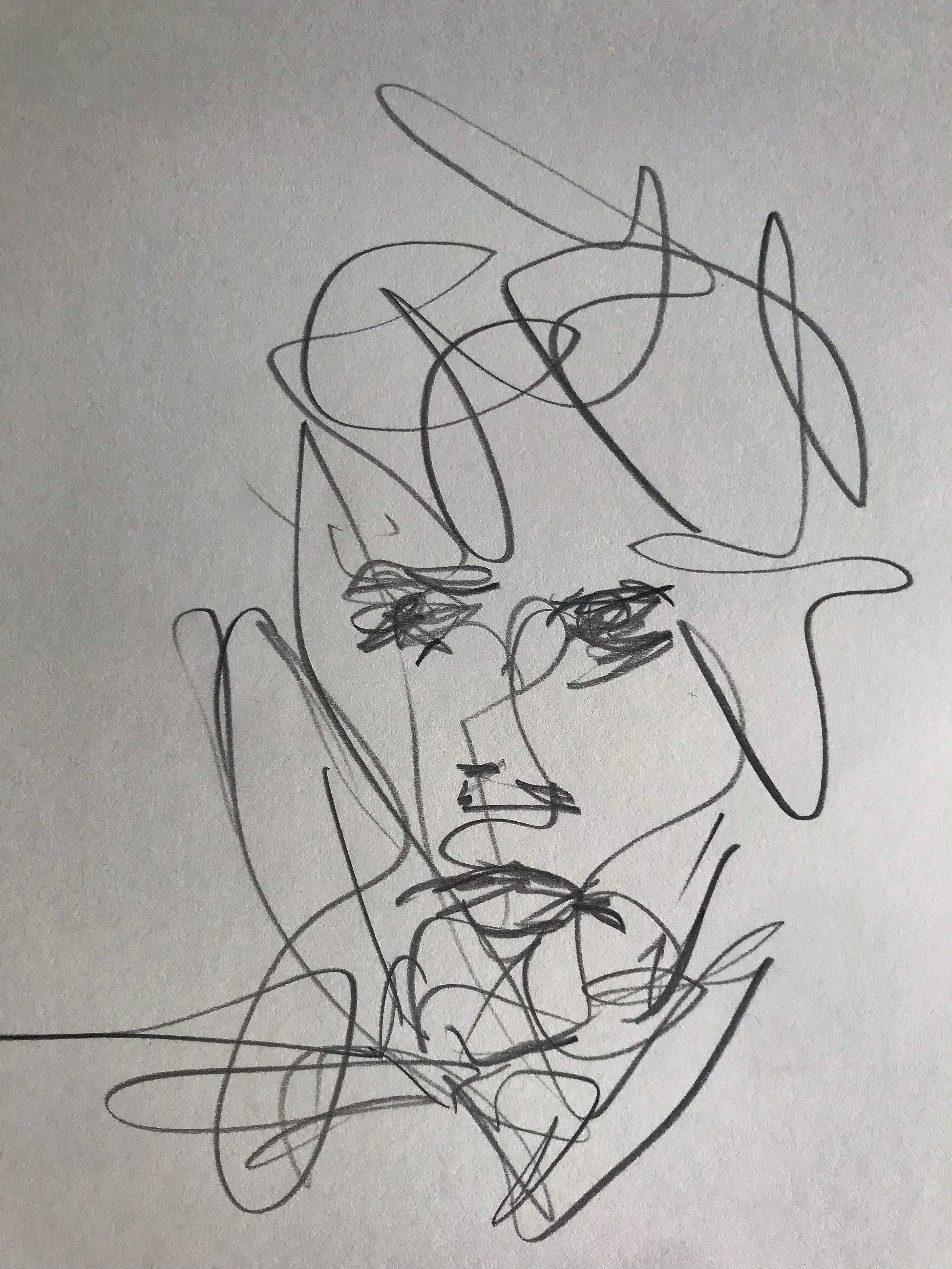

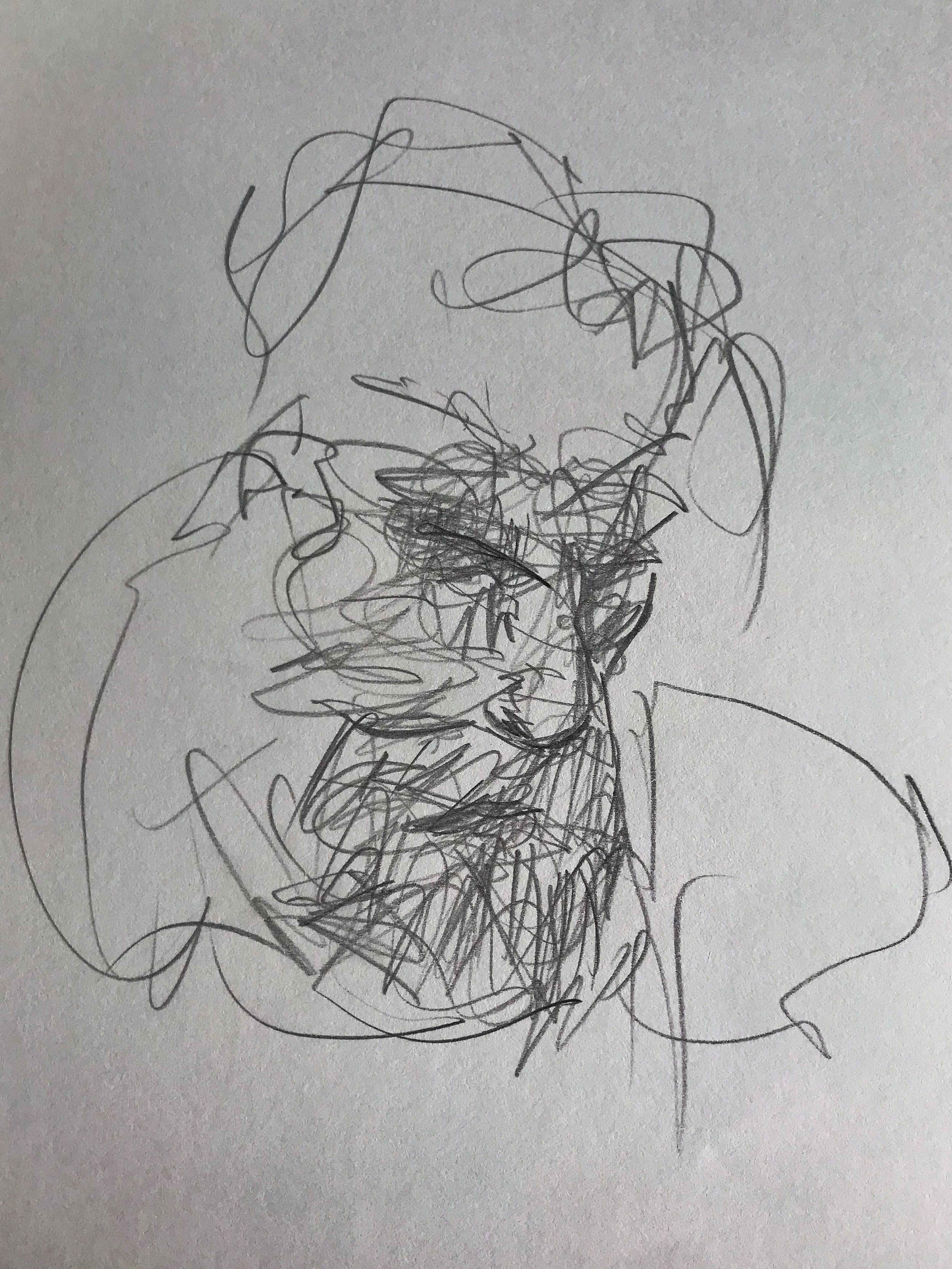

I brought a fresh sketchpad with me, a spiral-bound, A5-sized little thing with 50 blank sheets, perfectly ordinary. (There’s nothing ordinary about sketching, nor about the entire chain of people and events that causes a friendly sketchbook to be in my hands, to be “mine.” Perfectly extraordinary!) I thought I’d draw one sketch per sheet for the whole pad, a total of 50 sketches produced during this one museum visit.

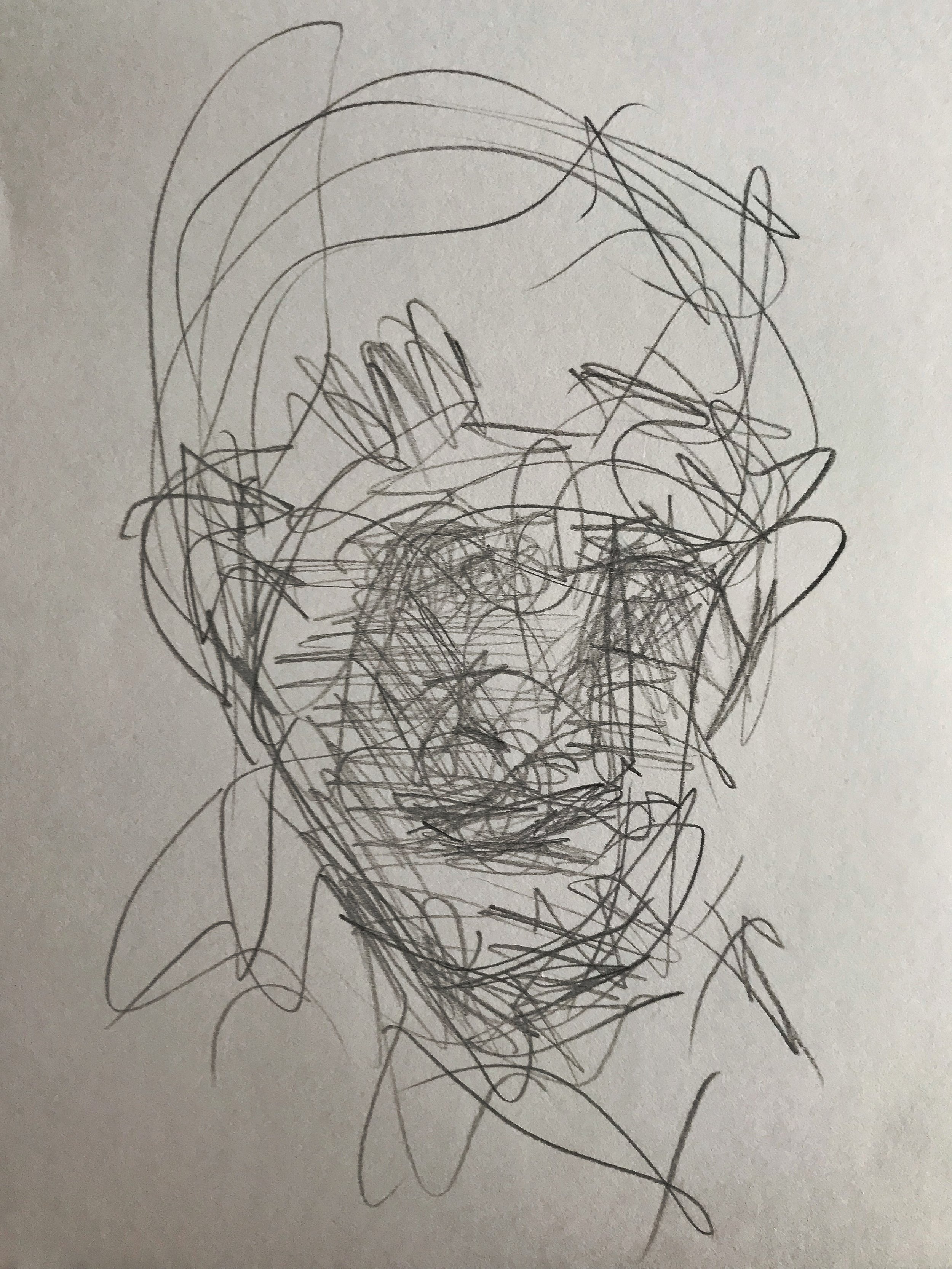

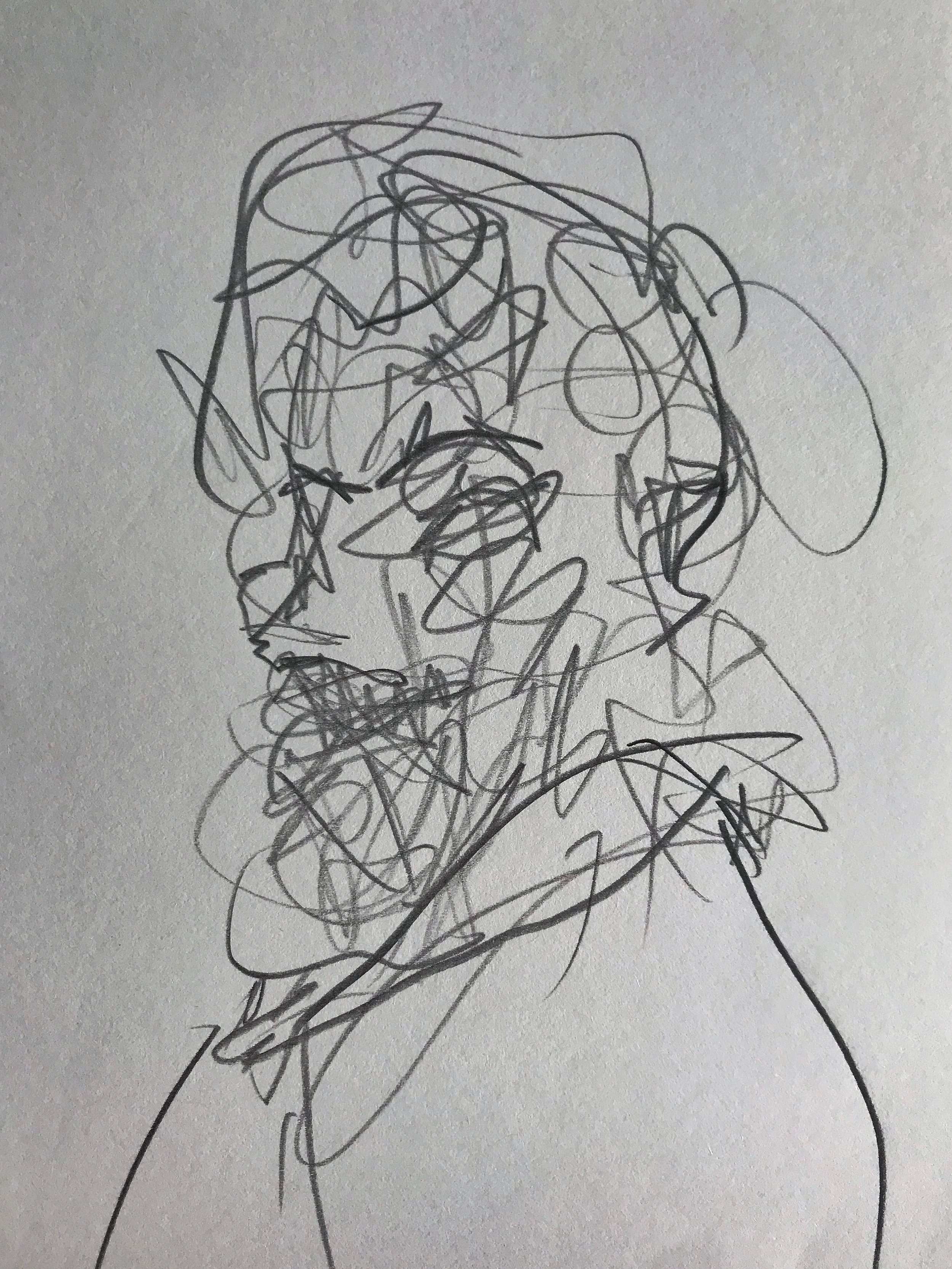

I probably spent about 75 minutes going from gallery to gallery, then on to the beautiful gardens in the back of the museum. Here’s the method: I’d park myself in front of a sculpture and start sketching immediately. I never looked at a label telling me who made the sculpture and who or what it depicted. Most things were by Rodin, I assume; but it’s possible that some pieces were made by a friend, an enemy, a lover, a teacher, a student, or someone linked to Rodin in some way. On this visit, it didn’t matter in the least. What mattered was my goal—50 sketches—and my process, my choices, my decisions, my behavior, my sketchpad (“mine!”), my pencils, my eyes, my brain, my heart, my history, my past, my present, my future, with an emphasis on my then-present, now-past. I was more important than Rodin, and still am! Forever and ever! And I’m not an egomaniac, now or ever! I’m not saying I’m a better artist than Rodin, I’m only saying that “I” was looking at Rodin’s work, and “I” had a unique perspective and perception—and so did everyone else at the Museum. It’d be impossible for me to look at a sculpture with Rodin’s eyes, or with my wife’s or my niece’s, or a tourist’s. My eyes, and my eyes only. “I am mine.”

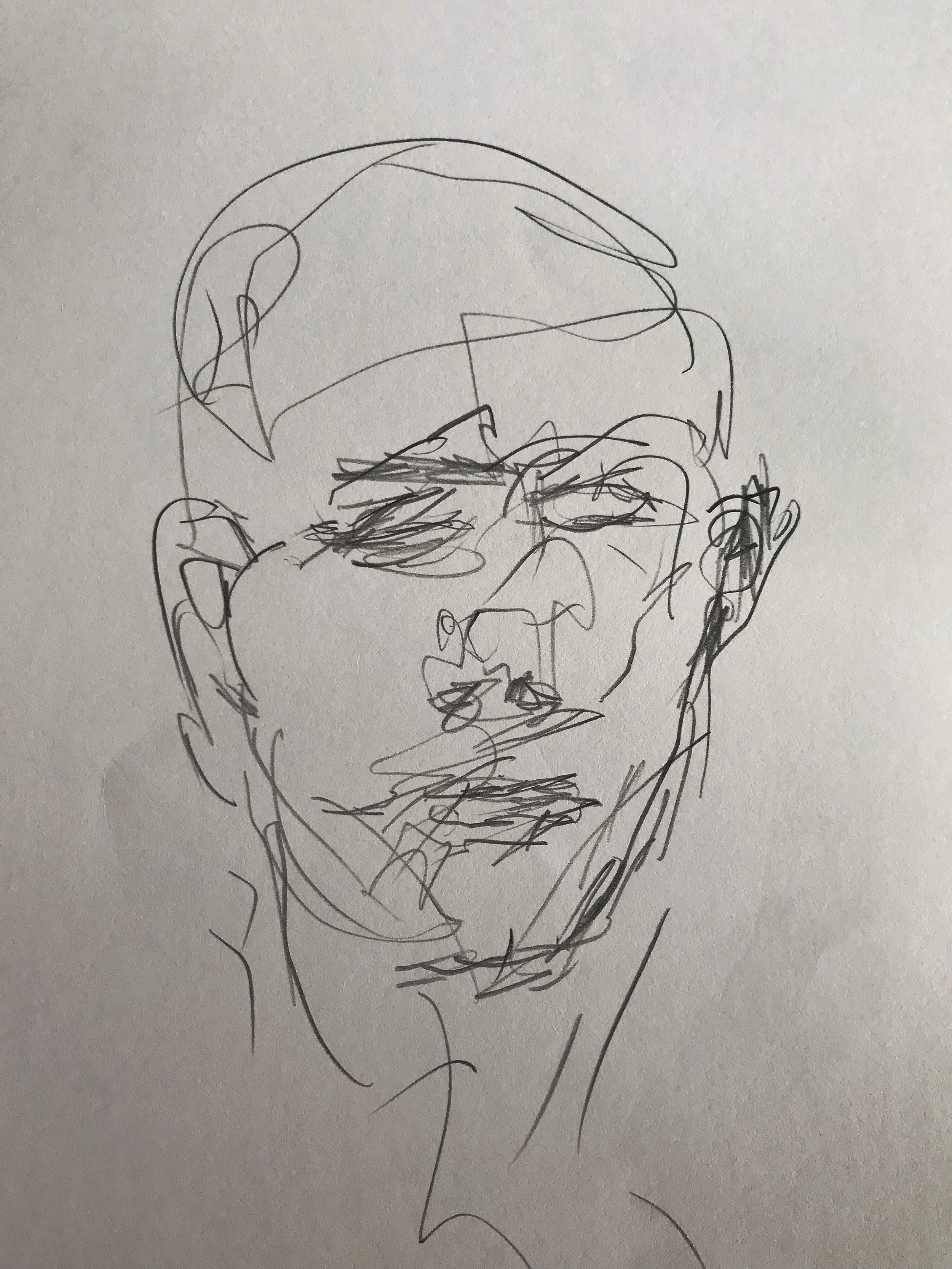

I’d choose a sculpture, deciding on which one after a few seconds’ thought. It wasn’t important. Any sculpture would do. I’d park myself in front of the sculpture or next to it, to its side, maybe behind it. It wasn’t important. And I’d sketch for ten seconds, twenty, forty-five seconds. Not important. I’d look without thinking much, and I’d scribble on the sketchpad without thinking much, and I’d capture or try to capture the gist of the sculpture (the gist according to my eyes, past, present, and future), or just have some subjective little head trip, and my hands would go zapty zapty, and I was done! I’d quickly turn the page and go park myself next to another sculpture, zapty zapty done!

I did it 50 times, about 35 or 38 of them inside the museum and the rest around the garden out back. It means I actually achieved the goal I gave myself, oh how disciplined, oh how low-standards, oh how fun.

Some museum goers don’t really look at anything. They amble through the premises, in boredom and impatience, just ticking off the visit on an informal list of things-to-do, places-to-see. Others are more attentive. It’s lovely to see a young parent with a very young child, the child amazed at some strange head or face or object, the parent keeping the child company or perhaps gently helping the child see the strange head. But the main thing is that I’d notice that some people wanted to look at the very sculpture I was sketching, and I’d interrupt my work and let them take my place, and they’d see or not see for a few seconds and move on, and I’d go back to my sketching position and finish my work. I ignored people, and I paid attention to people, and I did both at the same time. It’s a dynamic state of fluid attention, which in my informal neuroscience (I know nothing about the actual science of neuroscience) encourages the flow of love-everyone-dopamine. I loved the little kids looking at the strange heads, I loved the young parents, I loved the bored tourists, I loved Rodin, I loved the blobs that Rodin sculpted, and I loved my sketches, and I loved myself, and in my estimation I’m more important than Rodin, who’s dead and who’s immortal.

I’m almost one-hundred-percent sure that at least one person took a photo or a video of me sketching some blobby blob. And if I’m right, then it’s likely that social media now has a public register of an overweight middle-aged bald short-sighted amateur sketch artist doing a sloppy sketch of a blob in the Rodin Museum. Hey, do you think I interrupted my process to tell the tourist not to video me in my private moment? Hell, no. My process involved the tourist, my process required the tourist to register my process. Unconditional love is “involving.” Plus, my process wasn’t private. I wore my process like I wear a guy-bikini (you know, “show what you’ve got”) (and “it doesn’t have to be pretty”) (and a guy in a guy-bikini “isn’t pretty”) (and the guy-bikini and the mankini aren’t the same “thing”).

At the garden I noticed a young woman (I think she was 17 or so) standing near me, seemingly watching me sketch. And I swear she was smiling. And I swear on Rodin’s grave, may he rest in peace, I swear that the smiling young woman moved on with me when I went to the next sculpture in the garden, and she stood not far from me, slightly behind me, most likely watching how my head trip about Rodin was becoming a few pencil lines on a cheap little sketchpad. “I had a follower.”

But that isn’t important either.

Life is a labyrinth of paradoxes. The ordinary is extraordinary. The dead are immortal. Other people aren’t important, although you love them unconditionally. I think, therefore I am; I don’t think, therefore I sketch. I’m a speck of nothing, and I’m the center of the Universe, which according to certain theories is expanding at an alarming rate. Billions of years ago there was a bang, quite big! One thing led to another, and now I look good in a guy-bikini.

©2022, Pedro de Alcantara