Or I can experience the world by proxy: someone sitting not far from me is having a croissant with his coffee, and in my imagination I start tasting that croissant, chewing it, swallowing it, loving it by proxy because it’s someone else’s experience and sensation but I try to make it my own. Eat a croissant by proxy: weight-loss strategy.

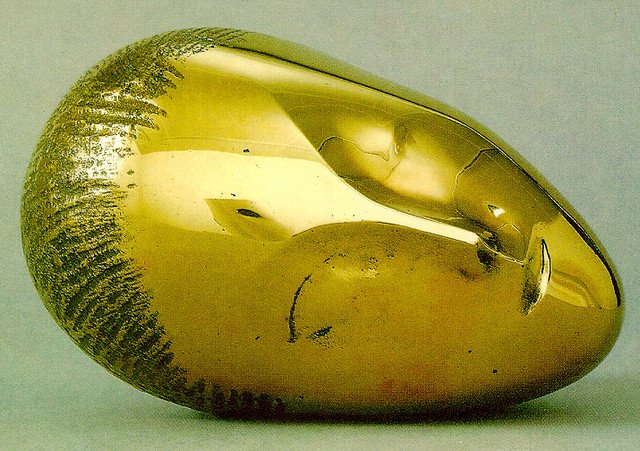

Five hundred years ago, a great painter (who happened to be a white male, but I think this isn’t too important) had a first-person, singular experience while in the presence of a woman (also white, but it’s just a detail). It’s not possible for us to know exactly how the painter was feeling, but we can suppose that he was, indeed, having thoughts, sensations, and emotions of many types, reacting to the woman, to the environment in which they were together, to the entire sociocultural context in which the man and the woman lived.

The man and the woman engaged in a deeply meaningful give-and-take. Every time the man took a breath he’d capture some molecules emanating from the woman, and vice versa. He saw the woman, he heard her, he talked to her. And she saw him, heard him, talked to him. A real molecule dialogue, in real time, analogical. Carl Jung would say—wouldn’t he?—that the man was meeting his anima, and the woman meeting her animus. In other words, an archetypal experience of infinite power. Having sex isn’t necessary for this archetypal encounter, and it’s extremely unlikely that Leonardo da Vinci had sex with Lisa del Giocondo.

But he did paint her, creating a record of their two-sided first-person, singular archetypal encounter (“ihre zweiseitige, singuläre archetypische Begegnung in der Ich-Perspektive”). You’re familiar with the painting, now called “Mona Lisa” and hanging in the Louvre in Paris.

The painting traveled in time and space, and it accrued (or gathered) tremendous historical power. It’d be easy to hyperlink from the Mona Lisa to just about any event in European history: Renaissance, Napoleon, monarchy, empire, republic, the French, the Italians, nobility, war and peace. Or any event in art history. Or anything, anywhere.

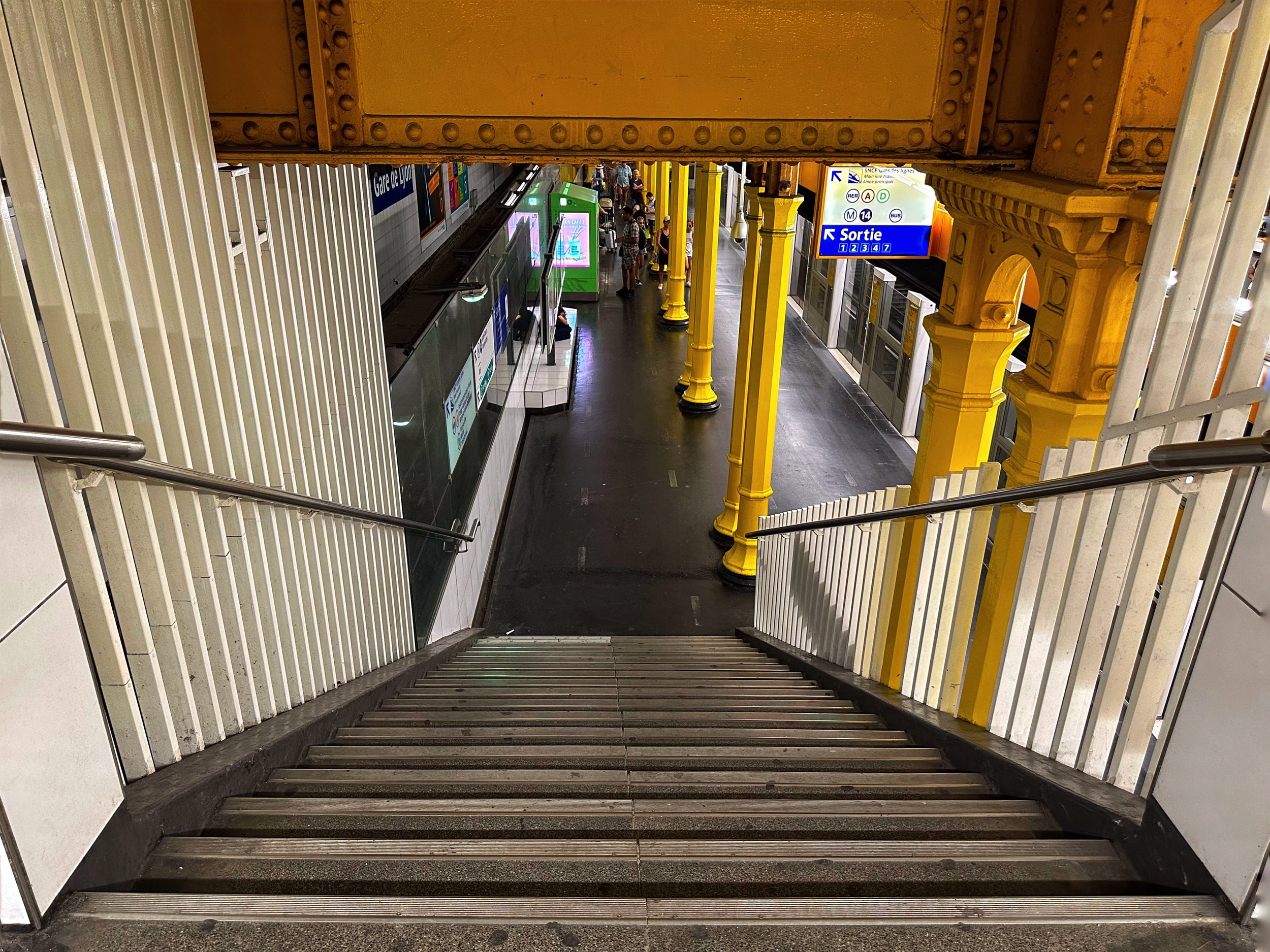

Never mind history, anything, anywhere. I’m in the Louvre, in relative proximity to the painting. The painting is protected by glass, and I can’t get any nearer to it than about two meters or so. And I’m surrounded by dozens and hundreds and thousands of tourists from every corner of the world, all of them having waited in a crowded line to stand for fifteen seconds two meters away from a painting protected by glass, and all of them taking selfies with their smartphones. And I too will take a selfie, standing in the crowd; and I’ll publish the photo on Instagram; and I’ll take a screenshot of my Instagram and publish it here.