The most generous thing you can do for everyone around you—and, indeed, for humanity—is to feel good.

It might sound shallow, ridiculous, selfish, and pointless, but many simple truths seem perfectly ridiculous before you wrap your brain around them.

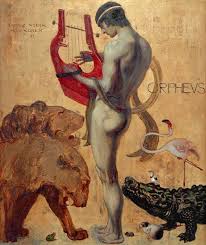

The reason why feeling good is your most urgent task is propagation. You put out your energies like a sprinkler in a garden. If you’re positive, you sprinkle positivity all around you. If you’re negative, you sprinkle it all upon the world.

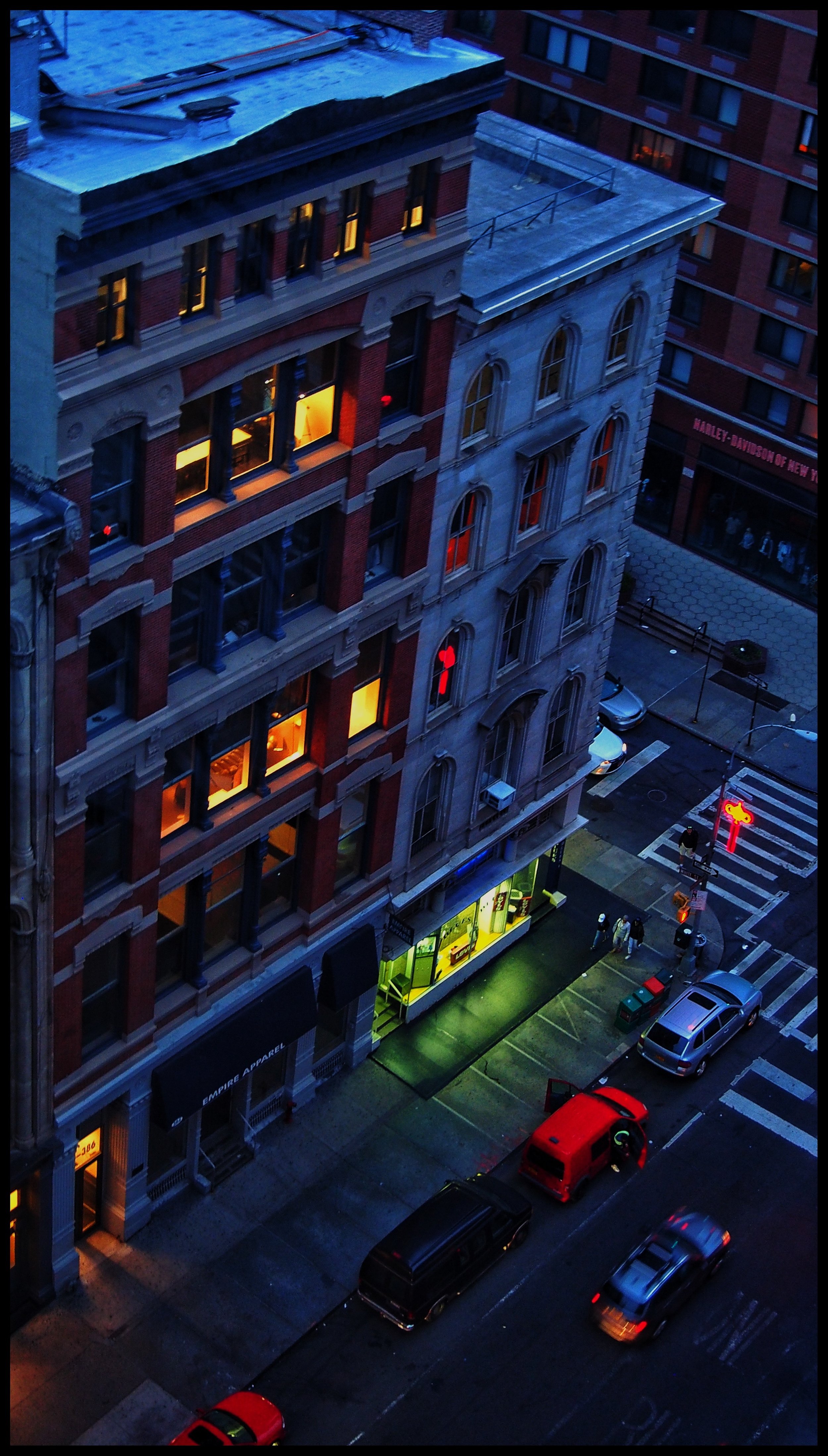

The principle is universal. The sun propagates light and heat. The ocean propagates wetness and a thousand other qualities. The infinite ocean, helped by the caressing sun and the sweet breeze, propagates healing energies to everything within its reach. You take a long walk on the beach, clear your mind, settle some longstanding issues, and return to the big city to work and to spread goodness.

You live as part of an interconnected web of human relationships, some very intimate, others so indirect you might not even be aware of them. A friend of a friend of a friend—someone you’ve never met and have never even heard of—affects your life without your knowing it. The friend of the friend of the friend sleeps badly, wakes up on the wrong side of the bed, and starts the day with a thoughtless accident in the kitchen while making breakfast. If the person in question becomes upset, annoyed, impatient, or angry, he or she will propagate these emotions to everyone else. The propagation might be brutal or discrete, but it’ll inevitably happen. The emotion sprinkles itself, and the friend of the friend will get it, and the friend will get it, and you’ll get it. By the time it reaches you, the emotion might be so diffuse as to be scientifically undetectable. But we won’t let science dissuade us from our simple truths!

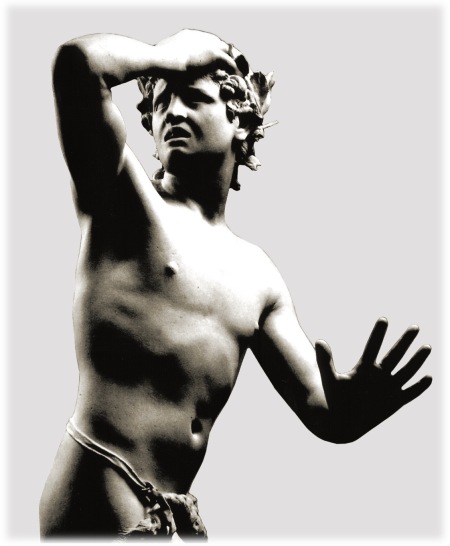

Feeling good is a skill that you can learn and practice. Although you receive other people’s energies incessantly, you aren’t a mere receptacle. You have agency—meaning, the power of choosing and of acting according to your choices. Standing in line at a cinema box office, you witness an agitated customer picking a fight with the hapless ticket seller. Then comes your turn. You can receive the previous customer’s agitation through the now-frustrated ticket seller, or you can give to the ticket seller a sympathetic smile and a kind word or two. You turn the tide, as it were, breaking the cycle of negative propagation.

Proportion, perspective, and distance are helpful. “Distance” is difficult to define, but I’ll say that it’s something you carry within you: a mental space; the capacity to look at yourself as if you were someone else looking at yourself; the capacity to “do” and “watch” at the same time. Most of us live safe and comfortable lives; our problems are manageable; we might be able to deal with these problems right here, right now, partly by not attaching too much importance to them. Many things in life are necessarily uncertain; looking for certainty and control will lead you astray and create frustration. Accept uncertainty and let go of control: this actually puts you in control. You’ll feel much better about yourself and about life, and you’ll end up propagating qualities of adaptability, curiosity, and gratitude.

Observe the triggers of positive and negative energy within you. Find out how much choice and leeway you have as regards your feelings and your behaviors. Become a student of propagation, sensing and understanding the eternal give-and-take between you and the world, between you and the other, between any one thing and any other thing. Then, go out and sprinkle your good feelings toward all and sundry.

©2017, Pedro de Alcantara