Coordination: Some New Ideas.

An excerpt from my work in progress, The Integrated String Player.

ONE EVENING SOMETIME AGO, a young woman on the verge of tears knocked on my door. I never found out her name, but I’ll call her Amanda.

“I’m a house guest upstairs,” she said, “and I can’t get in. There’s something wrong with the key.” She sort of shook her keychain at face level, to make sure I knew what she was talking about, or maybe just to show me she was upset.

“Let me go with you,” I said. I live on the second floor of a small four-floor building without an elevator. I followed Amanda to the top floor, and she proceeded to demonstrate how there was something wrong. She stabbed the keyhole with the key, and after several tries managed to insert the key in the keyhole. Then she twisted her body, and—nothing happened. The key didn’t turn, and the door didn’t open. She probably had spent a fair amount of time struggling with it before knocking on my door, and she was now at her wits’ end

“May I try?” I asked. I took the keychain from her hand, inserted the key in the keyhole, turned the key, and opened the door.It’s hard to explain simple things to people who are agitated. “You need to feel it,” I said—meaning, feel how the key goes in, how it opens the door if only you turn it. I closed the door and handed her the keychain.

She proceeded to stab the door and twist herself into a knot.

“Excuse me,” I said. I took the keychain again, moved the key slowly toward the keyhole, inserted it very slowly, and paused. “See? Then you hold the key lightly and turn your arm.” Without touching the key, I rotated my forearm in the air, so that she could see what I meant. Then I held the key, rotated my forearm, and opened the door. I closed it again. “Try it.”

She finally stood there in relative calm and opened the door. “Thanks,” she said, half-grateful and half-resentful. Then she disappeared into the apartment.

We tend to think of coordination as a physical skill, to be learned through physical means. We think some people are talented for it, and others are just “physically awkward and.” But Amanda demonstrates that coordination isn’t physical, and it isn’t even a skill. Rather, it’s a behavior or reaction, something that happens in real time moment by moment and that involves your perceptions of the world and of yourself, your intentions, suppositions, and fears. It’s not something you do; it’s who you are.

Amanda created a difficulty for herself, on account of emotions that resided inside her and that had nothing to do with the physical or mechanical aspects of opening a door. Then she amalgamated her emotions and the door, and determined that “something was wrong with the key.” The door was “bad,” the key was “bad.” And Amanda was completely and absolutely sure that the problem lay with the door and the key.

Her thinking was:

door

The actual situation was:

suppositions >> attitude >> coordination>> door

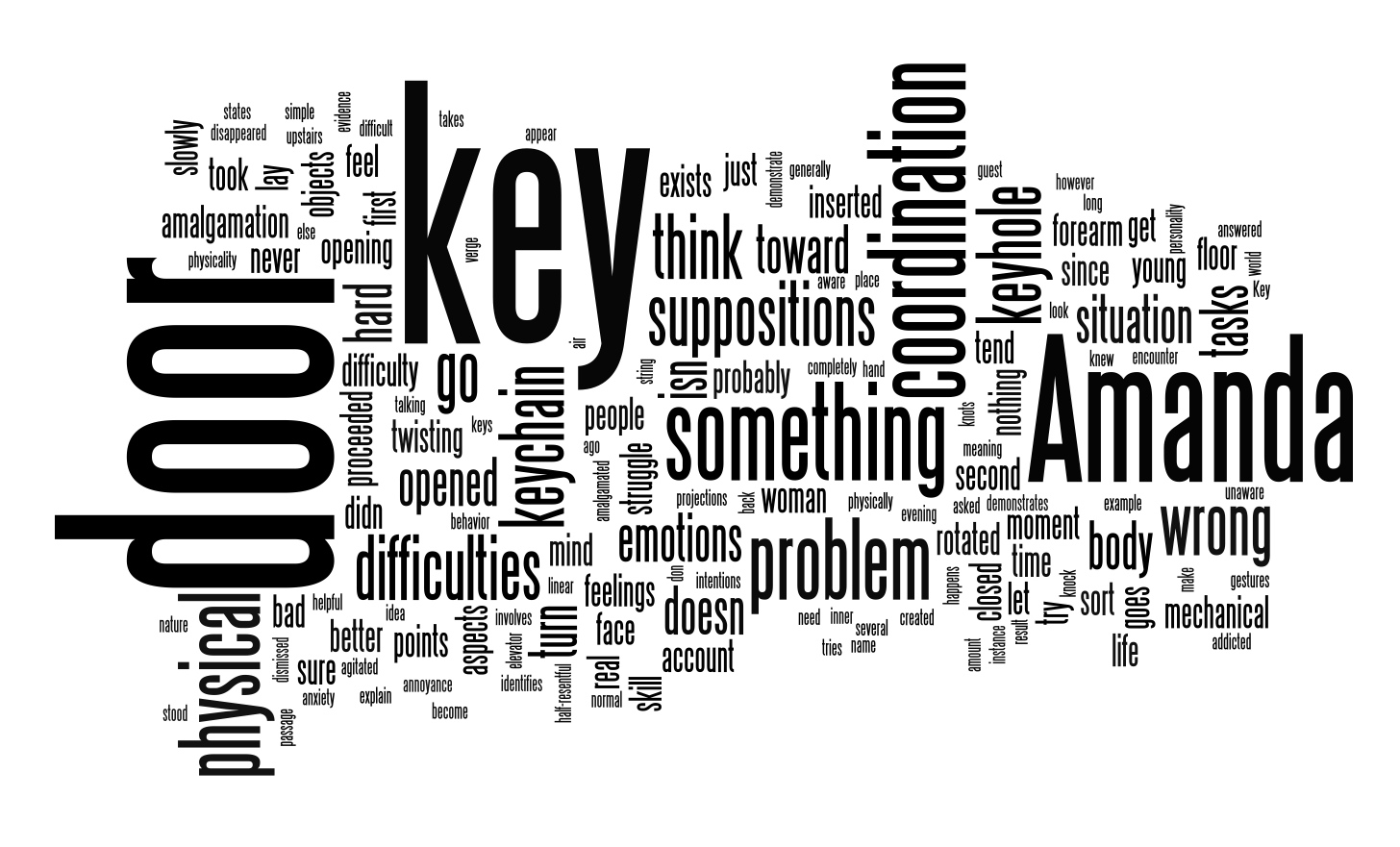

Even the representation above is misleading, since it looks linear and doesn’t account for the amalgamation of Amanda’s emotions, her physicality, and the tasks she was trying to accomplish. The Wordle figure below gives a better idea of what was going on.

In daily life and in music, what appear to be concrete, mechanical difficulties of coordination tend to be projections of your inner states. The difficulties exist first and foremost in your mind, where the amalgamation of emotions (anxiety, for instance), objects (doors and keys), and tasks (opening a door) takes place. And since mind and body are inseparable, the difficulties manifest themselves in gesture, action, process, and result—those aspects of your existence that “look like the body” to you. First you think that the difficulty “exists” in itself: something is wrong, the key doesn’t work, the musical passage is hard to play. Then you think that you might have a physical problem. But unless you go further back, to where you melded your feelings, your objects, and your tasks, you won’t be able to solve the problem successfully.

Amanda was certain that the problem lay with the key or the door, not with herself; and she probably dismissed our encounter as some sort of annoyance that she’d rather have avoided. The tendency for all of us is to be generally unaware of our suppositions and behaviors. We “don’t believe” evidence that doesn’t correspond with our suppositions. Amanda will continue twisting herself into knots as she goes from situation to situation—first, because she remains convinced that a problem exists with the key, the solution for which is her twisting herself; second, because she isn’t aware that she twists herself, and she feels her gestures to be necessary and normal; and third, she’s addicted to the struggle and identifies with it. She “is” the struggle, and to let go of it would mean to let go of her personality and become “someone else.”

These are the obstacles we all face in life, and in improving our coordination and our string playing.

Working on Yourself

It’s tempting to believe that, in order to play a string instrument well, you need to concentrate on the instrument and on the music you play—on technical challenges, the repetitive daily practice, the notes on the page. In actuality, when you play an instrument in practice or in performance, or even when you just think about the instrument, you’re directing your attention not to the instrument but to why you do things, and how you do them—and your “why” and “how” together determine who you are.

We’ll conduct a thought experiment. Take two musicians you’re familiar with. Let’s say Pinchas Zukerman and Anne-Sophie Mutter, although any two successful musicians will suit our purposes. It doesn’t matter whether you like or dislike them. What do you see and hear when they play? Two different human beings, playing in two different ways. They play very well, of course. But it’s not just a succession of notes that come out of their violins; it’s a succession of thoughts, emotions, habits, memories, choices, and decisions. You hear their life history, encapsulated in real time over the ninety minutes of their recital. You hear the sum total of their choices and decisions over decades, leading up to that moment—in which they’re still making choices and decisions. Our thought experiment suggests that Pinchas Zukerman is synonymous with the choices and decisions he’s made, is making, and will continue to make. Anne-Sophie Mutter is the embodiment of her own choices and decisions, many of which are quite different from Zukerman’s. Naturally enough you, too, are the embodiment of your unique choices and decisions.

The reason Zukerman and Mutter are so successful is that they’ve been making, for years on end, choices and decisions with a certain quality—purposeful, coherent, united in body and mind. In short, they’re attentive to their choices and decisions. When you charge each decision with the power of your attention, drawing the bow across the string becomes a meaningful event. So do all other gestures in string playing: dropping and lifting your fingers, adjusting your elbows for a big string crossing, plucking a string in pizzicato. The accumulation of meaningful gestures is the source of integration and success.

There are, of course, hundreds of different ways of practicing. But here’s a particular strategy that you might find useful.

1. Give yourself a task. This could be playing an open string, playing the opening phrase of a concerto, playing an improvisation, playing natural harmonics, and so on.

2. Do nothing at first. See if you can be in the presence of the task, so to speak, without reacting, without doing, without rushing, without hesitating, without judging.

3. Remind yourself of your own existence in body, mind, and soul. Find out where you are in space and time (which we discuss in detail soon). Get a sense of how the task relates to the larger picture of playing an instrument and making music, and also a sense of how you relate to the task in thought and emotion. What does drawing an open string, for instance, really mean to you? It creates oscillatory disturbances; it makes “noise” or “sound” or “music.” If you attune yourself to its vibrations, its fundamental and its multiple harmonics, the open string might strike you as divinely beautiful. The open string alters your personality in some ways; it gives you a new voice and it extends your energy field outward, to the extent where you might actually occupy an entire concert hall. In brief, an open string is a significant event, as are the tunes, pieces, and concert programs you prepare day by day.

4. From Amanda, the keyhole-stabbing maniac, we learned that there was a difference between “forcefully turning a key inserted in a keyhole” and “smoothly turning your forearm while holding a key inserted in a keyhole.” In the first instance, you become so invested in the task that you lose your head and sabotage the task; in the second, you keep your head and accomplish the task by primarily doing something constructive to yourself, rather than to the key or to the keyhole. This principle applies to everything you do at the instrument. For instance, you don’t really control your bowing; you control yourself in the process of drawing a bow.

5. Choose to perform the task, or not. It’s an essential step in the procedure, because it allows you to shape the entire decision-making process. In other words, at all moments you retain the ability to do nothing, the better to do anything you want.

6. If you choose to perform the task, go about it calmly and intelligently. There’s a lot to sense and enjoy when you don’t “attack the task.” Playing can be a boxing match or a dance. You can win the battle if you’re lucky, but it’s better not to engage in battle. And, in fact, the best boxers use rhythm and cunning rather than sheer muscle power.

7. Start all over again: Give yourself a task . . .

To change your playing, to improve it, to achieve your musical and professional goals, you work on who you are through your choices and decisions. The instrument is only a ruse or pretext for you to become attentive to yourself. As you work on yourself you might become more centered, or more open, or less afraid, or more agile, or more impetuous, or less impetuous. And, on account of all that, you’ll play and sound different.

Space and Time

Coordination isn’t a matter of physically organizing your gestures or your technique. Rather, it’s a question of noticing where you are and deciding where you’re going. Where you are in space and time? Are you in the present moment, or are you distracted or anxious about the past and the future? What’s your relationship to the environment? Do you interact with it positively, or are you shrinking inside it—shrinking while seated in an armchair, or shrinking as you chop vegetables? Why do you bump your head against a corner of the kitchen cupboard? It’s because of where you’re in space and time. Space and time are ever changing. Two seconds go by, and now you’re in a different time from where you were two seconds ago. You turn your head to look at something, and now you’re in a different space from where you were just before. At the kitchen, you bump your head against the corner of the cupboard because you weren’t, in space and time, where you needed to have been in order not to bump your head. If accidents come from being at the wrong place and the wrong time, it follows that coordination and good health come from being at the right place and the right time.

Your occupation of space and time, then, is at the heart of the bump, at the heart of the steps you take to go downstairs without falling, and at the heart of every last thing you do in your life—including every down-bow and every up-bow.

Space and time are difficult to define precisely. Philosophers and mystics have had murderous fights among themselves trying to clarify their meaning. But I think we can approach the concepts playfully, through daily activity, without killing anyone in the process.

Sit, and be aware of yourself seated in space. Rise, and be aware of yourself rising from the seated position. Walk, and be aware of yourself moving through space, or altering the form of space around you.

Sit, and be aware of the seconds going by as you remain seated. Rise, and be aware of the change in speeds as you pass from seated to rising. Going from rest to movement requires acceleration, and that means that one dimension of your time has now changed. Walk, and be aware of the transformations of space and time as you leave one little square foot of space to another, then to another, and yet another, second after second.

The awareness of space includes the objects you interact with: the chairs, tables, cars, buses, walls, windows, cupboards, and everything material that stands in your way or beckons you or is a help or an impediment to you. This includes your instrument. The awareness of space also includes air and light, temperature, humidity, and all the geophysical traits of the environment. And the awareness of space includes yourself—what you sometimes refer to “your body” in space, but which is really your person, in which body, mind, and soul are so intertwined that the body can’t possibly be said to have an independent existence. Your legs are made of flesh and bones, but also of your feelings about your legs, your memories of everything you’ve done with your legs, your accumulated sensations of using the legs or bumping the legs of having your legs caressed by your lover. The physicality of your legs is only one dimension, inseparable from psychological and emotional dimensions.

Although it’s ultimately impossible to compartmentalize these aspects of space, we’ll ponder them separately for the sake of practicality.

1. Explore the space of the environment.

A young person of my acquaintance came to visit me in Paris. It was his first travel outside his home country. The fellow was introverted and brainy, and as we went for walks around the magnificent city he kept his gaze downward, away from the architecture around him and the skies above him. I’m not even sure he saw the sidewalks themselves; I think he dwelled mostly inside his head, occupied with his thoughts and theories.

It’s easy to ignore the environment and separate oneself from it. So, the task is for you to be in the space, open to it, attentive, observant. It doesn’t have to be Paris. A shopping mall will do, as will your home, your car—wherever you are, and at all times. Let your awareness embrace perspective, light and shadow, straight and curved lines, horizontality, verticality, symmetry, asymmetry. Start sensing how it feels when you look up at the world or down at it, when you walk along narrow streets and when you cross broad avenues, when you pass from the sun to the shade and back again, when you enter a busy shop and when you exit it. Perhaps you hate busy shops and you think you don’t need to know anything else about it. But deciding to become consciously aware of space and of your reactions to it can sometimes alter your habitual reactions, your loves and hatreds. As a “spatial anthropologist,” so to speak, you might visit the hateful busy shop and dispassionately notice a thousand interest details—not only about the shop, but about yourself as well.

Your spatial awareness is, to some degree, inseparable from your aural awareness. A shop, a street, a park, and a practice room feel very different to you because they sound so different one from the other. And you occupy each environment partly according to your aural response to it. In the next chapter we’ll study aural awareness and its contribution to your total awareness.

2. Explore the space of the object.

As our friend Amanda demonstrated, coordination involves the constant interaction with objects: keys and keyholes, of course, but also chairs, tables, desks, cupboards, bathtubs, and a hundred others. For us string players, the objects include our instruments and bows.

Each object is “space, delineated.” Imagine an empty room; now imagine the same room with a single armchair in it. The armchair alters the room’s space. Depending on the circumstances or depending on your own subjectivity, you may see the alteration as positive or negative; the room may become more comfortable or less comfortable, more elegant or less elegant. But the fact is that the armchair inevitably alters the room. Similarly, your string instrument “alters you” once you start handling it. The cello can invade your personal space, causing you to shrink and twist uncomfortably; or expand your personal space, making you feel as if you double in size. This is also true of the violin, the viola, the bass, and all other instruments.

It’s good to have a notion of the size, shape, and weight of your instrument “in itself,” that is, separately from what it does to your personal space once you start handling it. In other words, your instrument has an objective existence and a subjective one; and the subjective existence, which involves your sensations, thoughts, and emotions, can become healthier if you can “size up your instrument,” literally as well as symbolically. It’s easy to be blinded to a visual reality on account of habit; you don’t see the dust on your bookshelf unless you actually decide to look at it with some intentionality. This is also true of other senses, including smell, hearing, and touch. It means you can have distorted or incomplete sensorial feedback as regards your own instrument, despite having played it for many years or perhaps because of it. To sense your instrument more objectively, start by looking at other people’s instruments and handling them whenever possible, developing the “skill of seeing.” In time you might see your own instrument with more intelligent eyes.

Place your own instrument in unlikely playing positions, and you’ll be surprised at you’re your perceptions of the object’s size, shape, and weight change—as if the instrument itself became bigger or smaller, heavier or lighter. There are musical traditions in North Africa and in India, for instance, where seated violinists put their instruments on their lap, sometimes playing them as if they were little cellos or gambas. In my musical explorations I’ve held the cello flat on my lap; upside down, resting on my right tight; under my chin, as I stand; upside down against my sternum as I walk around the concert hall, singing to the audience and strumming the cello to accompany the song. These postures have technical, acoustic, and musical merits that are integral to the compositions I perform. But even if you choose never to perform in strange postures, handling the instrument in unorthodox ways will enhance your awareness of the instrument’s spatial qualities, benefitting your habitual playing in normal positions.

3. Explore the space of your person.

Becoming aware of your spatial decisions and their consequences is useful, regardless of what decisions you make. If you put on tight jeans, you’re making a spatial decision. In itself, the decision isn’t good or bad; the tight jeans could make you uncomfortable and awkward all day long, or they could trigger a pleasant sense of your legs’ power to assert themselves in opposition to a restraint.

Judgment tends to interfere with awareness, polluting it with overly subjective filters and suppositions. Tight jeans can make you feel strong and they can make you feel weak; and it’s possible to prefer the sensation of weakness to the sensation of strength. The tightness of your jeans is a technical matter, so to speak—something that you can measure with a tape. The sensations and emotions that come with wearing the jeans are a perfectly natural, biological response; sensations are the necessary entry point toward awareness. But the judgment of whether it’s good, bad, right, or wrong to wear tight jeans comes “after the fact,” so to speak. If you want to be an expert in the awareness of self-space, you need to live many spatial experiences to the full, without letting judgment predetermine what types of spatial experiences you may or may not have.

Ideally, it goes like this:

experience >> sensations >> discernment >> judgment

It’d pervert the process if you let it become like this:

judgment x experience >> judgment x sensations >> judgment x discernment

Your awareness of self-space, to coin a term, comes from a thousand things in your daily life: how you fit in your clothes and shoes, how you take the shape of a couch or the couch takes your shape, how you carry a violin case, how you stand with the violin case hanging from your shoulder as you wait for a bus, how you negotiate a crowded bus while carrying your violin case. If you’re distracted, with your mind projected into the past or the future, you’re unlikely to assess your self-space objectively. It can be useful, then, to give yourself leisurely tasks of observation.

On a free day, take your violin case for a walk, much as you’d take the dog for a walk. Sense your strides, sense whether you bump into things and people, whether you scrunch your self-space in fear of dropping the violin, whether you feel proud of being a musician carrying precious working tools or embarrassed and apologetic. Do you want the girls to notice your violin case and think that you’re cute, or are you afraid to look like a nerd? These emotions manifest themselves spatially—as do all emotions, without exception.

Another useful exercise is ask yourself innocent little questions about your body. You don’t need to answer the questions; the simple fact of asking them makes you more alert about your orientation in space. What is the distance between your earlobes and your shoulders? Where is your belly button? How many elbows do you have? How big are your armpits? Are buttocks necessary?

Your spatial awareness is like a tree strung with thousands of lights. Each question you ask yourself energizes a string of lights somewhere in your consciousness. Triggers of awareness aren’t always rational or intellectual. Sometimes a single silly question—absurd, illogical, irrational, and unanswerable—can light up the entire tree.

Containment, Latency, Direction

The section below introduces three concepts that I cover more fully in the companion volumes Indirect Procedures: A Musician’s Guide to the Alexander Technique and Integrated Practice: Coordination, Rhythm & Sound. It’s possible to consider this section as self-contained, requiring no further reading; or to take it as an invitation to study Indirect Procedures and Integrated Practice in depth.

1. Containment

Coordination is an encyclopedic subject. Pondering it, you might study posture, breathing, anatomy, physiology, neuroscience, martial arts, sports, and dance (to name just a few). How to start? There are many useful entry points, among which I propose that you use what I call the simplified skeleton. It focuses on three important zones that merit your attention: the connection between the neck and the spine (leading to the poise of the head), the connection between the back and shoulders (leading to the agility of the arms), and the connection between the back and pelvis (leading to the agility of the legs).

Although the neck is quite mobile, moving it too much or too often tends to put a strain on the neck itself directly and the rest of the body indirectly. Suppose you nod when you talk. It’s possible to nod discreetly, using the joint between the spine and the skull and otherwise leaving your neck stil;, or to nod more vigorously and move the whole neck as you talk—in which case the neck breaks away from the spine, as it were, and assumes a life of its own. Generally speaking, it’s better to get your neck to behave as if wholly integrated into the spine rather than autonomous from it. Find out where your neck is in space, make it subservient to the spine, and “tell it to stay there.”

Suppose you get into violin-playing position. You lift your left arm to bring the violin up, and you lift your right arm to bring the bow up. It’s only too easy to involve the shoulders a bit too much, lifting them too high or contracting them. Generally speaking, it’s better to get your shoulders to behave as if primarily integrated into the back and only secondarily involved with the arms. Find out where your shoulders are in space, make them subservient to the back, and “tell them to stay there.”

Suppose you walk to the bus stop carrying your cello or violin. With each step you risk letting the legs drag the pelvis just a bit too far away from the back. Then the pelvis behaves as if it belonged with the legs, so to speak. As a result, your body gets wobbly and you tighten your neck and shoulders to compensate for the lack of power in your back. Generally speaking, it’s better to integrate your pelvis into a flexible unit with the back, and only secondarily involved with the legs. Find out where your pelvis is in space, make it subservient to the back, and “tell it to stay there.”

The simplified skeleton, then, is a way of both thinking and moving in space. Its fundamental quality is containment. Contain your neck, shoulders, and pelvis; then, do anything you want. Needless to say, containment isn’t a purely physical quality but a way of living, an aesthetics that we’ll study throughout this book. The simplified skeleton is discussed in detail in chapter 2 of Indirect Procedures, which includes multiple exercises.

The young lady in the clip below is a past master in the art of containment.

2. Latency

Moving is good and necessary, and any impediment to free movement is an impediment to your health. On that we all agree at once. Counterintuitive as it may be, however, the capacity to resist and oppose movement is equally good and necessary. If your spine didn’t offer some resistance to weight and pressure, carrying a backpack while walking would cause you to stumble and fall. The capacity to resist is innate to all vertebrates. Before your birth, the walls of your mother’s womb exerted considerable pressure upon your little, little skeleton—and you resisted the pressure and survived it because your little, little skeleton was perfectly designed for the job. Resistance is the springy quality of the string on your cello and of your bow. The springy bow meets the springy string, and the result is marvelous sound; without resistance, there would be no sound. Your fingers, hands, arms, shoulders, back, and legs aren’t dissimilar to the string and to the bow, in that they too are capable of springy resistance.

Although resistance is essential, two obstacles rise on its path. First, you might attach negative connotations to the word resistance, or to the very idea of meeting weight and pressure with a force of your own. “It sounds wrong,” you might say. Second, when resistance is well distributed throughout the body, it feels so good you might want call it “relaxation,” and perhaps deny that the lovely feeling arises from actual resistance.

Your cello strings are forever ready to resist the pressure of your bow. We might say that the strings contain latent resistance, held in reserve and ever ready to be employed. The latency becomes actualized once you apply pressure, weight, or any force upon the string. Similarly, your body and its inseparable mind contain latent resistance, which becomes actualized when you play, when you carry an instrument case, and in countless ways whenever you do any one thing.

When you move, you retain your latent resistance, which you may use or not as you see fit; when you resist, you retain your latent mobility, which you may use or not as you see fit. The collaboration of mobility and resistance is the hallmark of good coordination. And their collaboration requires that both qualities be latent at all times. In fact, once you start thinking about it, you’ll realize that you’re a living web of latencies—that is, skills and potentialities that you hold in reserve inside you. The more latencies you hold, the richer you are; resistance and mobility are but two of your many latencies.

Resistance and mobility are discussed at length in Indirect Procedures. Latency is discussed at length in Integrated Practice. Both books have extensive indexes, which you can consult to find all the relevant passages and sections.

3. Direction

Containment and latency are related qualities. We might say that latency refers to what you hold inside you, and containment refers to how you hold it. You hold latent thoughts, energies, emotions, gestures, and all sorts of creative possibilities. And your manner of holding them inside you is what you often call “posture” or “attitude,” a sort of vessel for your thoughts.

Vital as it may be, holding your latent possibilities is only half of the coordinative process; the other half, equally vital, consists in choosing those possibilities that you’ll render visible and audible in action. Moment by moment, you pull a possibility out of latency and give it a form, a sound, a physical reality; then you choose the next one; and the next, again and again. Thought becomes energy, shaping itself as a bow stroke, a series of notes, a shade of coloristic vibrato, or anything else. We’ll call this half of the coordinative process direction. It’s the marriage of mind and body, intention and gesture, deciding and doing; and it happens in real time, all day, everyday.

Coordination, then, is your way of shaping your thoughts and energies. Uncoordinated thoughts result in wasted energy; coordinated thoughts result in directed energy. Choosing and deciding what you want to do are just as important as the details of your orientation in space, such as “where to place your elbows.” To improve your coordination, work on your capacity to make directed decisions, and your elbows will follow!

Direction is discussed at length in Indirect Procedures; chapter 5 is wholly devoted to it. It’s also discussed throughout Integrated Practice. As with latency, the books’ indexes will help you find the relevant passages.

Coordination and Personality

Standing, walking, sitting, lying down, running, swimming, playing the cello, and all other activities in your life are never purely physical, or even primarily physical. They are inextricably bound with cultural, linguistic, and social dimensions. Take standing, for instance. It’s easy to consider it a posture, an arrangement of body parts, “a stack of bones,” where the main thing is for you to figure out how to align your feet and legs with your upper body. But look at a partial list of expressions in the English language that involve standing, and you’ll see how attitude, posture, personality, cultural mores, and other dimensions all work together:

Stand ground, stand on ceremony, stand in awe. Stand out from the crowd, stand out like a sore thumb, stand out a mile, stand shoulder to shoulder, stand tall. Stand up and be counted.

Let’s conduct a thought experiment. Visualize, in your mind, a group of archetypical Argentines dancing the tango at a café in Buenos Aires. The music—played by the bandoneón, double bass, and piano—has a strong pull with just a hint of a marching rhythm to it. A singer expresses strong, dramatic emotions with a well-trained, nearly operatic voice. Her language, the Argentine version of Spanish, carries distant echoes of Arabic, which her ancestors spoke centuries before. The overall posture for most people in the room is very erect, the sternum a little lifted as if in defiance of convention or authority.

Now visualize a group of archetypical Brazilians dancing the samba at a bar in Rio de Janeiro. An untrained singer sings a sad-sweet song about the sunset. Her language, the Brazilian version of Portuguese, is made of soft sounds and verbal caresses. The singing is accompanied by a cavaquinho, which looks like a toy guitar, plus three or four percussion instruments of African origin. The song is mellow and swinging, and its rhythms are full of subtle syncopations and off-beats that make the downbeats a little hard to place (unless you’re born to it). The overall posture for most people in the room is relaxed; someone marks the tempo with her shoulders, someone else with her hips, a third person with her shoulders, another with her feet.

Our thought experiment involves a bit of cultural stereotyping. Not every Argentine dances the tango, and not every Brazilian is samba-crazy. Plus, there exist many styles of singing and dancing both the tango and the samba. The essence of the experiment, however, rises above stereotyping and lets us understand that movement and coordination are seeped in linguistic, cultural, and environmental factors. We’ll say there exists a “tango body with a tango mind,” and a “samba body with a samba mind.” One comes with the other; there is no tango mind with a samba body. You can of course learn how to dance the tango and how to dance the samba, but for each dance you’ll need the appropriate frame of mind, complete with its language, personality, and identity.

Everything you do at your instrument has a coordinative component, which you normally think of as posture, movement, hand-to-eye coordination, position of feet, rotation of the arms, angle of head and neck, and so on. But every coordinative component is inseparable from your personality and identity. You hold the violin just so, because “you are just so.” Lower the violin, or raise it, and the bodily sensations and the emotions that come with them risk being “foreign” to you, much as the Argentine tango mind feels foreign if it tries to occupy the Brazilian samba body.

Technical challenges at the violin, then, are primarily challenges of identity. If you’re modest and retiring, you might balk at sounding “too loud.” But how to play a concerto with a symphony orchestra in a big hall? Or let’s suppose that you’ve been struggling with back pain, the solution for which might require that you stop hyperextending your spine when you play. But unless you hyperextend your spine you don’t feel that you’re expressing yourself. Consciously or unconsciously, you end up preferring the problem to the solution, because the problem is “you” and the solution is “foreign to you.”

Identity is everything to you, as it is to me and to everyone else (including our friend Amanda, she of the keyhole). Your clothes, eating habits, and speech patterns—just to make a partial list—define who you are. So do your bow strokes, your vibrato, the position of your feet, and every technical and musical aspect of string playing. And when it comes to identity, there are no easy changes, simple cures, or immediate results.

There’s a subtle interaction between your inner core and your periphery. Is it your inner core that determines what shirts you wear? Or do your choice of shirts affect your personality and transform you, a little or a lot? (If you don't know for sure, put on a Hawaiian shirt and find out how you feel.) Are your choices of a sitting position and a bow grip the natural emanations of your inner core? Or can you become “a new person” by sitting differently at the cello and changing your bow hold? When you practice the cello you are, in fact, dealing with these questions directly or indirectly.

Here are a few suggestions to get you thinking.

1. Become aware of how music making is an embodiment of identity. Watch fellow musicians practicing and performing, or go on YouTube and see how Mistislav Rostropovich and Janos Starker (just to choose two examples) aren’t just two opposing techniques or bodily postures but two different identities or “souls,” if you will. Then you’ll realize that you can’t work on technique or coordination separately from your identity or soul.

2. Become willing to try things that feel wrong to you: bow strokes, bow holds, seated postures, standing postures, ways of bending your fingers, arrangements of elbow and shoulders, and so on. Be “foreign” for a moment, and see how well you can cope with a new bodily identity. It might involve some play-acting, some clowning, jokes and laughter. Or it might involve a courageous psychological act that is, in fact, painful and yet necessary for your growth.

3. Study the art of letting go. Start with an object, for instance; let go of a knick-knack on your bookshelf and give it to a student, a friend, or a passerby. Or throw it away, period. Then let go of a habit like chewing gum. Instead of engaging in the habit, notice and acknowledge it. Catch yourself craving oral satisfaction, and decide to “crave” instead of “satisfying your craving.” The distance you get from looking at the habit, so to speak, will make the disengagement easier. Then let go of habitual verbal tics, perhaps refraining from a swear word that you tend to use too easily. The practice of letting go of little things will help you let go of weightier things: an old posture at the cello, fixed ideas about vibrato, certainties as regards your career, habits of breathing, and other things that may be costly to your health and freedom.

Throughout The Integrated String Player we’ll continue to study coordination in its multiple dimensions. The exercises and concepts in every chapter are, without exception, “coordinative.” This is obvious for exercises involving bow changes or left-hand shifts, for example, but less obvious when it comes to interpretation. In truth, your aesthetics is in fact synonymous with your coordination. Your bodily gestures are a reflection of what you believe in as an artist and storyteller. Therefore, chapters and sections that deal with improvisation, music theory, the conversational approach, and other musical matter are also studies in coordination.