Isn’t it strange that you can practice law, practice the piano, have a spiritual practice, and practice for your wedding?

Maybe it’s just a play on words. Or maybe the word “practice” itself is rich in meaning, and therefore useful to us. It comes to us from Greek, via Latin.

Greek praktikos "fit for action, fit for business; business-like, practical; active, effective, vigorous," from praktos "done; to be done," verbal adjective of prassein, prattein "to do, act, effect, accomplish."

To act, to accomplish; effective, vigorous. And “not theory.” Not in your head, not in a book, not a dogma, not dead. Practice must be a doing, even if you practice it in a Zen-like non-doing manner.

For our purposes, we’ll define it as something that you do regularly, in a committed and organized manner, leading to an increase in awareness and presence. It exists in a thousand forms, including the professional set of skills learned and performed with a particular frame of mind (to practice law), the creative set of skills borne of exercising specific gestures over weeks, months, and years (to practice the piano), and the quest for connection with the ineffable through prayer, meditation, song, and sacrifice (to have a spiritual practice).

How to practice practice, so to speak? Walking works beautifully for many people. Decide to walk every day—perhaps to and from work. Or perhaps as a break from work: a walk in the park, or pacing the rooftop terrace of your office building and thinking about life over a hundred rounds of a very short walk, back and forth, back and forth. Walking the dog is a practice.

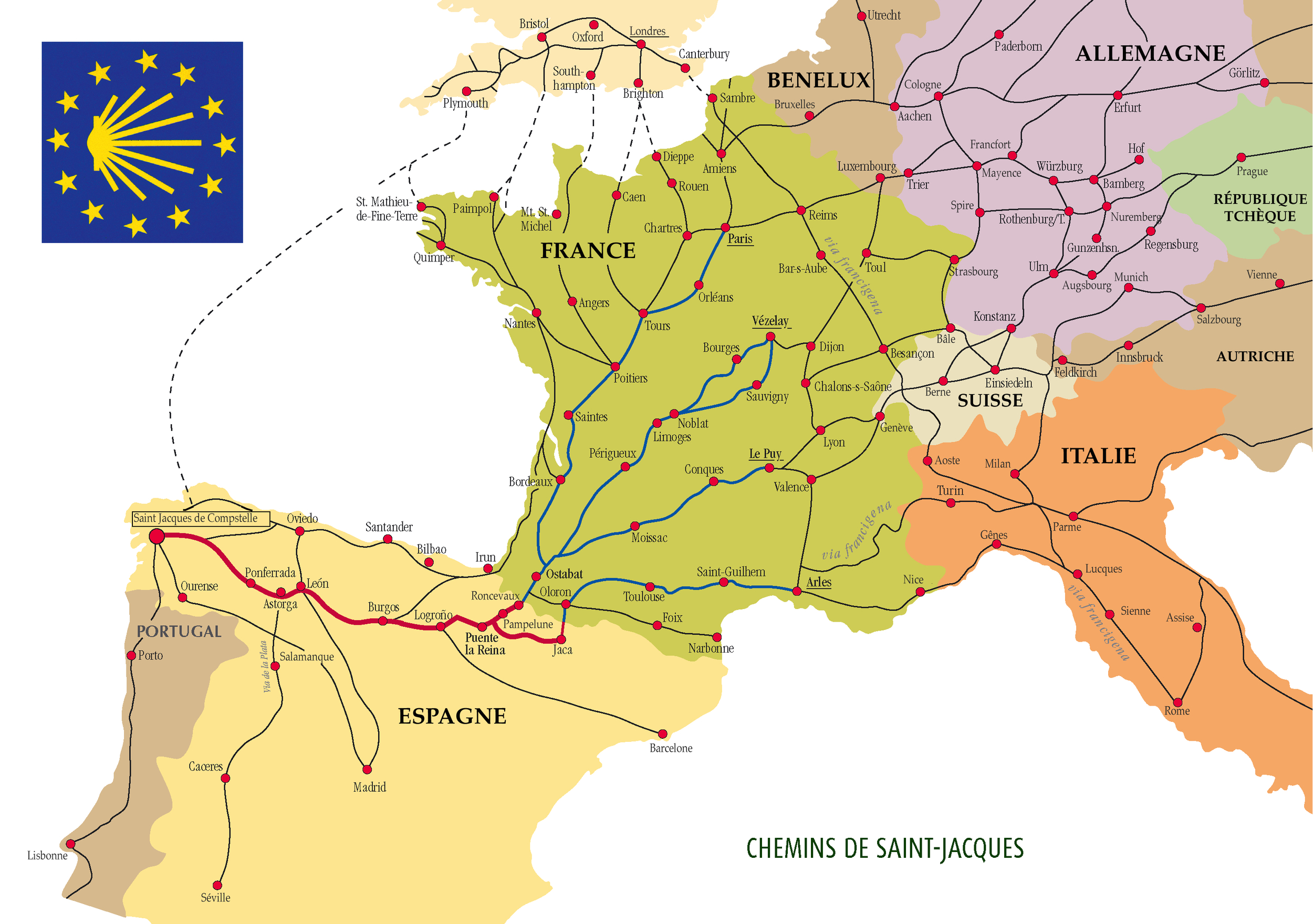

You can get serious and take the Road to Santiago, the pilgrimage first established in the 9th century. Walk from somewhere in Western Europe all the way to Santiago de Compostella in northwestern Spain.

Or decide to walk barefoot, full-time or part-time. My friend John does it full-time, and he’s, like, oh man, so alive! Inspired by John, I started walking barefoot part-time three years ago. There have been whole days in which I stayed barefoot, including in winter, out in the rain, or riding public transportation. It’s an exercise in awareness and in not-worrying-about-what-people-would-say. And it happens to be extremely pleasurable.

Another practice is committing to a time and a place, and going there on a regular basis. It could be the street market every Sunday, for instance. Plan your meals, interact with the fruit sellers, watch people, taste fresh foods, enjoy life.

Or go to Starbucks frequently and use it as an office, for creative work or for office work. You can go to the same café many times in a row, or to a different café each time. Both have merits. The main thing is to go and be there, doing something again and again over weeks and months. You’ll meet people at your Starbucks office, make friends, become attached to the place and its neighborhood. And you’ll get your work done. How different is it from going to a corporate job and sitting in a cubicle looking at a computer screen? Perhaps it’s the same thing; or perhaps the cubicle can become the same thing—that is, a practice—provided that you find the attitude that transforms a constraint, imposed by circumstances, into a commitment you choose to make, with the result of your becoming alert and present.

Spiritual practice takes a thousand shapes. Here’s one: going to church every week, or perhaps most days, or perhaps every day, or perhaps twice a day. One of my devout friends calls the institution of the church a vessel for his spirituality.

My friend considers that there is no spirituality without a vessel. Dwelling in the vessel is a practice, whether the vessel is material (a building) or symbolic (a paradigm and an institution). Perhaps it’s the practice that matters, rather than the vessel. Or perhaps the vessel counts for something. All I know is that entering temples, cathedrals, chapels, and basilicas, in Paris and in my travels, is always transformative. I wonder what would happen if I did it every day, without exception.

A lifetime commitment to the church is, of course, a very formal and deep practice. Other spiritual practices are more informal. Some formalists pooh-pooh the informalists. But that's OK; the informalists pooh-pooh the pooh-pooh.

You can practice a simple exercise, returning to it often and over a span of years. In sports there are many such exercises: the golf swing, the free throw in basketball, the rope skipping of a boxer. Here’s a kind of warm-up stretch. Sit on the floor, with legs bent; bring the soles of your feet together, and hold your feet with your hands; try to lower your knees until they touch the floor; now lean your trunk forward. Do it once or twice, and it comes across as an uncomfortable and possibly useless exercise. But do this one stretch every day for twenty-five years, and you might discover all sorts of dimensions, to the exercise and to yourself as you respond to the exercise.

The form of your practice—yoga, Tai Chi, tango—might be very important . . . or not. After all, every form has its enlightened practitioners and its zombies. Shadow boxing could be as integrative as an ancestral martial art. Air guitar? You bet. “Star Wars” lightsaber play-acting? Of course. The main thing is to commit to the practice and to do it with all your heart.

And then there’s the practice of a creative skill, whether you do it professionally or for pleasure alone. A drawing a day, for instance—fast or slow, as you wish; take thirty seconds or thirty minutes. Choosing pencils, sharpening them, leafing through a sketchbook, translating the swirling images of a street corner into arm and hand gestures that make marks on paper . . . if you think about it, the act is by no means banal. It’s transformative in many ways. Do it steadily over days and months, and something will get reorganized inside yourself: the way you look at the world, the way you absorb and interpret information, the way you pay attention.

The practice is primary, the skill secondary; or, to put it differently, it’s only by practicing that you gain the skill. You might want to say, “But I don’t know how to draw!” Sure, sure. That’s why you practice, you dummkopf!

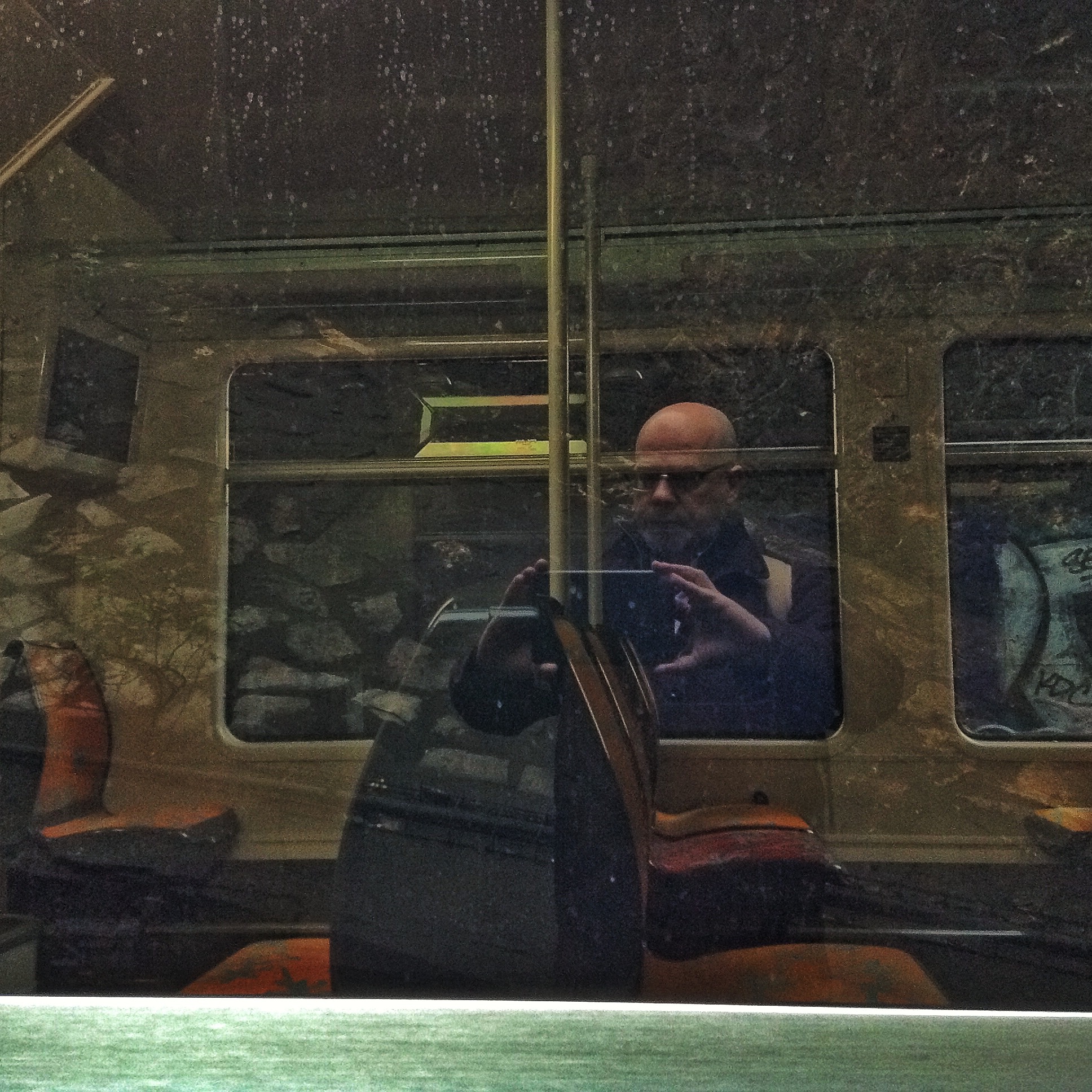

A smartphone and an Instagram account, and—hey, presto! You can practice photography. Publish crappy photos of pizza slices if that’s your thing. Or develop the art of perceiving, thinking, and deciding. Photography is the reason or excuse (or vessel) to open up your mind and heart.

Walking, going to the market, stopping at Starbucks, visiting a monument, taking photos with your smartphone . . . Is there any difference between practice and life?

Nah. Life is an Integrated Practice.

© 2016, Pedro de Alcantara